how are you today by the Manus Recording Project Collective

James Parker

& Joel Stern

Offshore

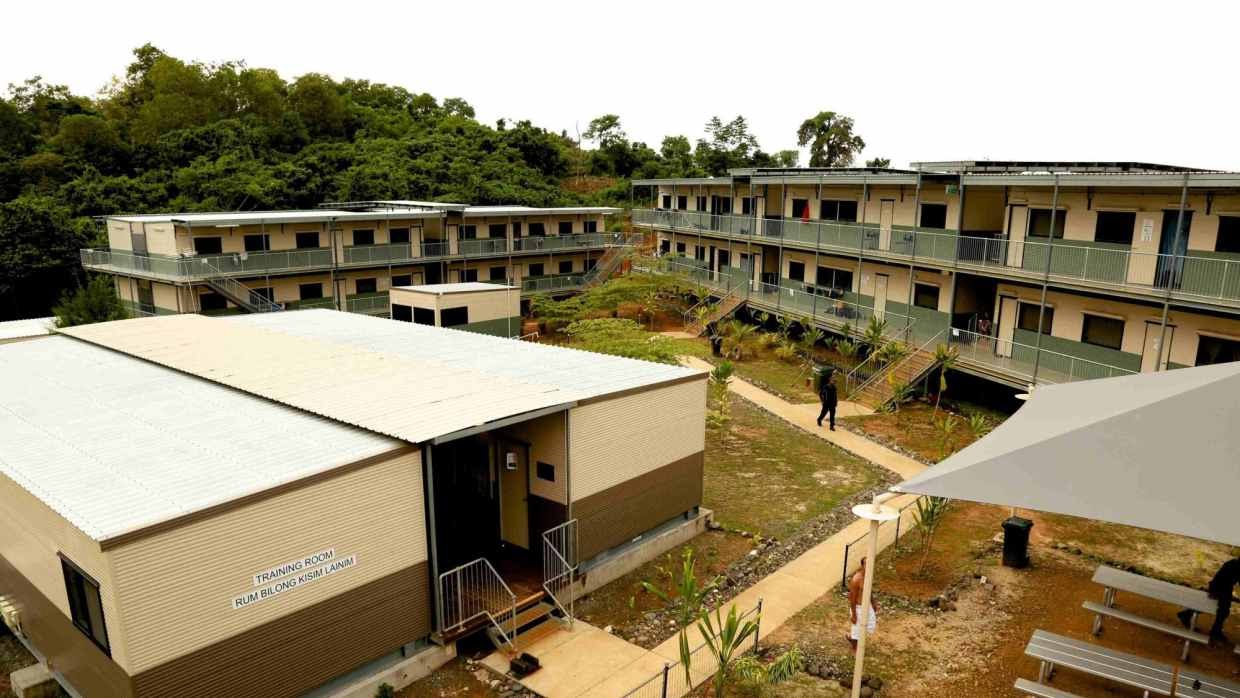

From 2013 to 2017, nearly 2,000 men who had arrived in Australian territory seeking asylum were forcibly transferred to Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island and detained at the Manus Regional Processing Centre (MRPC) at the Australian government’s expense. It was unclear how long they would be there. Conditions at the detention centre were difficult in the extreme. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) described them as ‘punitive’, having ‘severely negative impacts on health, and particularly significantly mental health.’1 Detainees themselves spoke less euphemistically of ‘agony’, ‘humiliation’, and ‘torture.’2 On this final point the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture agreed.3 By 2016, the UNHCR was finding rates of depression, anxiety, and PTSD affecting over eighty per cent of the incarcerated community, the highest recorded in the medical literature to date.4 Suicide attempts were common. Some, tragically, were successful.5 Both Australia’s transfer policy and the conditions of detention themselves, the UNHCR wrote, ‘do not adequately comply with international laws and standards.’6

In October 2017, Manus Regional Processing Centre was officially closed, the Papua New Guinea Supreme Court having declared it unconstitutional eighteen months before, 7 and the men were directed to relocate to smaller facilities in Lorengau, also on Manus. Most refused, citing fears for their safety in the community, and anxiety at ‘what would happen to them once the centre had closed, and the Australian Government washed their hands of them’.8 In order to force them out, the authorities eliminated provisions and removed the generators powering the facility. Instead of leaving, the men self-organised a stand of resistance against their involuntary and indefinite detention. By 23 November, the remaining men had been violently evicted by police and security contractors and relocated to other ‘accommodation’ on Manus.

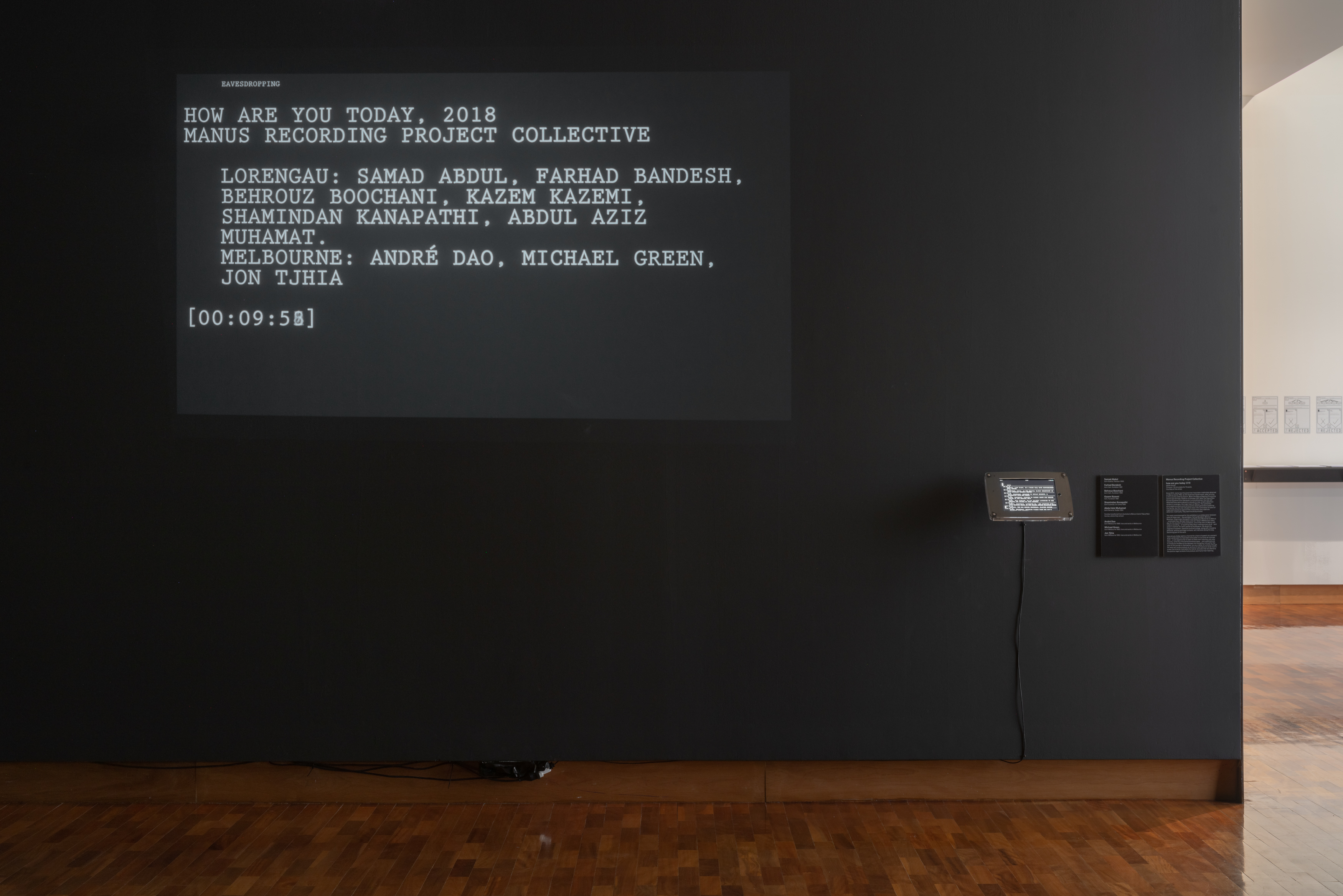

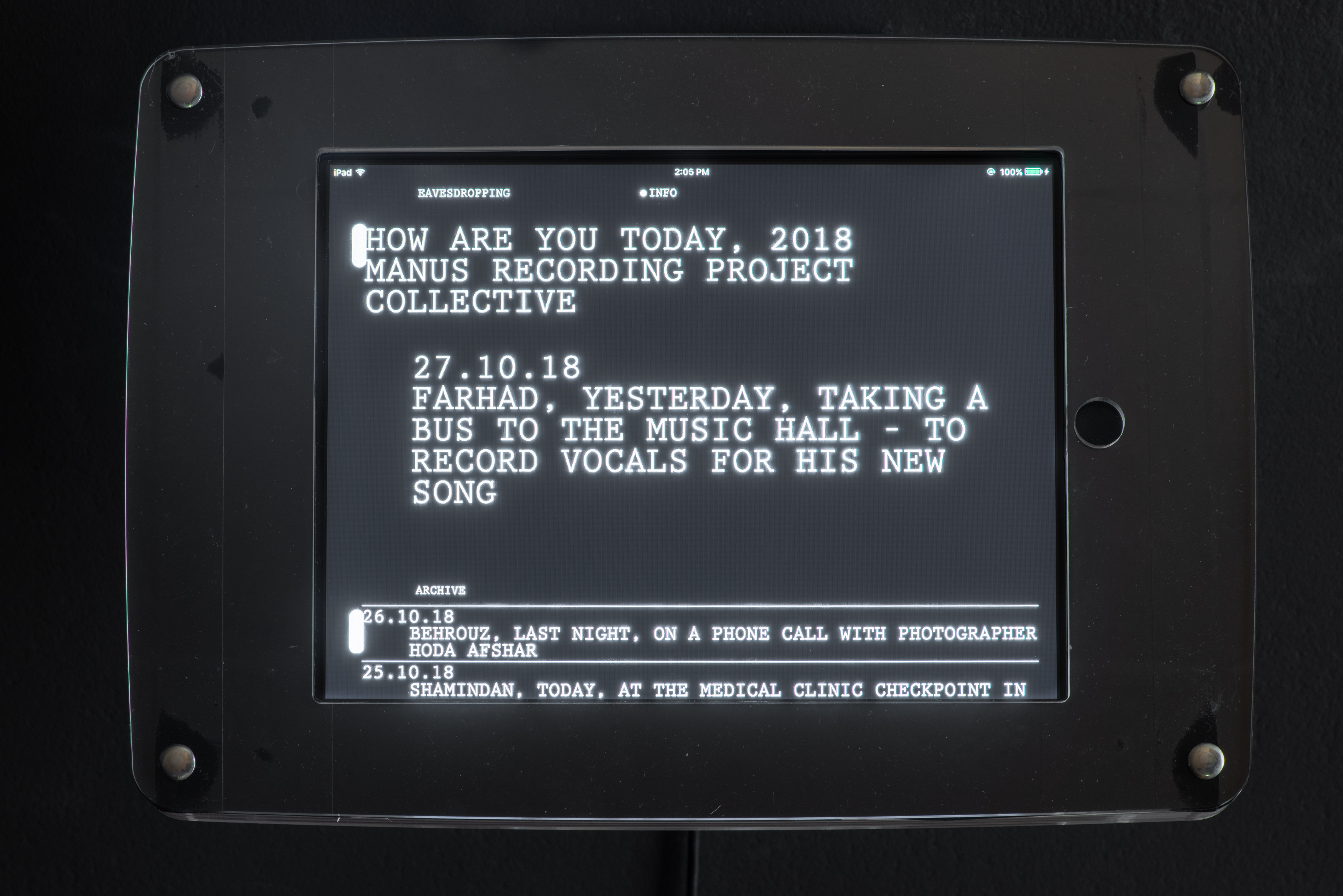

how are you today is an artwork produced by six of these men — Abdul Aziz Muhamat, Behrouz Boochani, Farhad Bandesh, Kazem Kazemi, Samad Abdul and Shamindan Kanapathi — along with Michael Green, André Dao, and Jon Tjhia, their collaborators in Melbourne (en masse, the Manus Recording Project Collective). The work was commissioned in 2018 for an exhibition called Eavesdropping at the Ian Potter Museum of Art, at the University of Melbourne, the largest University-based museum in Australia. Each day for the fourteen weeks of the show, one of the men on Manus made a sound recording and sent it ‘onshore’ for swift upload to the gallery. By the exhibition’s end, there were eighty- four recordings in total, each ten minutes long. The result is an archive of fourteen hours — too large and diverse to synthesise, yet only a tiny fraction of the men’s indefinite internment.

This essay introduces how are you today, along with a series of reflections on it, including by two of the artists. We see our task as twofold. First, to document the work’s conception, production, and key realisations, both for the record and to spare the pieces that follow the trouble. Second, to offer a curatorial perspective in the process, since we were the ones who commissioned how are you today at the end of 2017.

The essay proceeds chronologically, starting with The Messenger, a podcast produced by four of the artists from the Manus Recording Project Collective, and which led to the work’s commissioning. Though how are you today shares many common themes with The Messenger, drawing out the two works’ many deliberate differences — of style, form, audio-fidelity, scale, setting — is also, we hope, instructive. From there, we move on to describe how are you today’s conception in relation to and as part of the broader project of Eavesdropping, along with some of the risks and curatorial challenges involved in realising it.

What has always been striking about how are you today curatorially speaking is how many of these challenges related to, or came to be refracted through, legal processes, and imaginations. Both the gallery and the University frequently appealed to law as the privileged language and mechanism for resolving ethical, practical, and political questions, even where it wasn’t obvious in advance that legal institutions or frameworks had, or ought to have, jurisdiction. Right from the start, how are you today was a work of law as much as a work of art. This fact alone is not so remarkable. Law’s constitutive role in the production of all art as art has, of course, been widely noted.9 What was remarkable with how are you today, however, was that law was being asked to do so much work, so conspicuously, and with such important consequences for the work’s eventual meaning and effects.

If law always governs the relationship between artists and a gallery, and describes the various rights and obligations over the work; if in doing so it brings the work into being in a certain way, indeed establishes its status precisely as a work; with how are you today, and unlike every other work in the show, so many of the standard terms had to be renegotiated or fought for, and so many novel legal questions were raised. It wasn’t just a matter of determining artist fees, the terms of the work’s display and so on, but also: the legality of communications from Manus Island to Australia, third party intellectual property rights; what would constitute meaningful consent from the artists; the distribution of risk in relation to possible controversial; traumatic or even defamatory content in the recordings; the gallery’s rights to censor or otherwise intervene in the staging of the work; even the men on Manus’ very status as artists. Indeed, in a final perverse but extremely telling instance, just days before the show opened the gallery would insist that jurisdiction over the text used to describe the work on the institution’s own walls fell to the Supreme Court of Papua New Guinea. Recording and thinking through these details matters, we think, because they capture something important about art-law relations in general, about the specific artistic, legal, and political climate out of and into which how are you today emerged, and therefore also about the meaning of the work itself.

In so many ways, how are you today unsettles the distinction we commonly make between a ‘work’ and its ‘context’. Though it comprises fourteen hours of audio, these are emphatically not, or not just, field recordings, to be listened to either for their aesthetic merits or documentary fidelity; even if some of them are undeniably beautiful and the audio quality is often high. What we hear when we listen to Aziz cooking or Kazem showering is both the powerful normalcy of such activities and how radically their meaning is transformed by the violence of their setting, as constituted by the laws and politics of offshore detention. Likewise, in the recordings made on 27 July 2018 and 7 August 2018 respectively we don’t just hear the sounds of the Manusian jungle and the Pacific Ocean, but also Behrouz and Samad listening to them, six years into their captivity, along with the strangeness, perhaps, of experiencing all this in a gallery as a leadership coup unfolds in which the current and former immigration ministers battle it out to unseat prime minister Malcolm Turnbull. how are you today insists that we attend to both its ‘cochlear’ and ‘non-cochlear’ dimensions: the dialogue between what is and isn’t ‘heard.’10

-

UNHCR, ‘UNHCR Urges Australia to Evacuate Off-Shore Facilities as Health Situation Deteriorates,’ UNHCR (The UN Refugee Agency), October 12, 2018b.

https://www.unhcr.org/en-au/news/briefing/2018/10/5bc059d24/unhcr-urges-australia-evacuate-off-shorefacilities-health-situation-deteriorates.html ↩ -

Behrouz Boochani, ‘This is Manus Island. My Prison. My Torture. My Humiliation’ The Guardian, February 19, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/ commentisfree/2016/feb/19/this-is-manus-island-my-prison-my-torturemy-humiliation ↩

-

Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, A/HRC/28/68/Add, (March 5, 2015), 1.https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session28/Documents/A_HRC_28_68_Add.1_en.doc ↩

-

Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 2015. ↩

-

ABC News, ‘Manus Island Refugee Dies in Apparent Suicide,’ ABC News, May 22, 2018. https:// www.abc.net.au/news/2018-05-22/manus-island-refugee-dead-afterjumping-from-moving-bus/9786852 ↩

-

UNHCR, ‘Submission by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees on the Inquiry into the Serious Allegations of Abuse, Self-harm and Neglect of Asylum Seekers in Relation to the Nauru Regional Processing Centre, and Any Like Allegations in Relation to the Manus Regional Processing Centre,’ (2016), 1. https://www.unhcr. org/58362da34.pdf ↩

-

Namah v Pato (2016) SC1497. ↩

-

Amnesty International Australia and Refugee Council of Australia 2018 ‘Until When: The Forgotten Men of Manus Island’ (Amnesty International Australia and Refugee Council of Australia: 2018).

https://www. refugeecouncil.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Until_WhenAIA RCOA_FINAL.pdf ↩ -

Jacques Derrida, Before the Law: in Attridge D ed Acts of Literature (London: Routledge, 1992). ↩

-

Seth Kim-Cohen, In the Blink of an Ear: Toward a Non-Cochlear Sonic Art Continuum (London: International Publishing Group, 2009). ↩

Behrouz, the day before yesterday, walking in the jungle in the morning

This dialogue is ongoing. In the next part of the essay we detail the work’s two most significant realisations to date, at Ian Potter Museum of Art in 2018, and at City Gallery Wellington in 2019. Each time the work is shown, as the recordings become increasingly ‘archival’ and the status both of Manus itself and the men detained there changes, how are you today changes too. We hear it differently because the work is no longer what it was. This is what Desmond Manderson means,1 following Mieke Bal and Didi Huberman,2 when he advocates ‘anachronism’ in art history and criticism as well as in jurisprudence. The work of art, like the law, he says, is ‘always speaking’: always simultaneously a function of the contexts and histories that animated it, in the past, and the questions it animates, in the present. The work’s meaning does not exist at either one of these poles, therefore, but precisely in their tension. Indeed, to a large extent, that tension is the work.3

The Messenger

The story of how are you today begins with The Messenger. In 2016, Sudanese refugee Abdul Aziz Muhamat (Aziz)4 began sending WhatsApp voice messages to Melbourne journalist Michael Green, using a smuggled phone in detention on Manus. Over two years the men sustained a prolific correspondence, totalling more than 3,500 messages by the project’s end. These formed the basis of The Messenger, a podcast series made by Green, along with André Dao, Jon Tjhia, and producers at Behind the Wire and the Wheeler Centre.

The Messenger is remarkable in a lot of ways, but one thing that stood out immediately was that it enabled us to hear Aziz speak — at a time when debates about Australia’s offshore detention regime tended to exclude refugees’ voices almost completely. This was not an accident, of course. As Peter Chambers has pointed out,5 offshore is a form, not a place. It is a jurisdictional and (an)aesthetic technology, whose spatial and auditory features are essential to its political effects. Offshore not only invisibilizes those subject to it, it silences them — or at least puts them out of earshot.

Together, ‘Australia’s immigration department, and the governments of Nauru and Manus, [had] made it very difficult for journalists to communicate with detainees. Visitors [weren’t] allowed to make recordings, and the people who came by boat weren’t initially allowed to use their own phones,

Green explains early in The Messenger’s first episode. Even on the rare occasions the Australian mainland did hear from refugees on Manus before 2017, what was heard tended to be highly mediated, whether by politicians, journalists or through the sanitising discourse of human rights. This was the logic The Messenger set out to subvert, even if it could not, of course, do away with mediation entirely. ‘We wanted to have detainees speaking about their experiences, rather than hearing the government’s policy justifications’, Green would later explain.6 And sure enough, hearing Aziz out loud, in his own words, against the odds, definitely ‘not a boat number’, came as a real shock both in Australia and elsewhere, where the podcast quickly won accolades and awards.7 The Messenger demonstrated that, in the hands of Aziz and his collaborators, a microphone, an internet connection and the creative appropriation of the WhatsApp messaging service had the ‘capacity to expose and breach the secrecy that obscures and sustains the system of offshore detention.’8

This breach was more than simply testimonial. It wasn’t just a matter of relaying the horrific conditions experienced by detainees on Manus, describing their debilitating psychological effects, or narrating acts of resistance and advocacy on the part of Aziz and his friends. Aziz gave compelling accounts in each of these respects. But his voice wasn’t the only thing that made it off Manus in the ‘voice messages’ he sent Green in Melbourne. There were a whole range of other sonic details too, each one an opening onto the soundscape and other conditions of this peculiar form of incarceration.9 Ten minutes into episode one, for instance, we hear music in the background as Aziz recounts his daily routine. Green is embarrassed by his own surprise. ‘Where are you playing that?’ he asks. ‘Is that playing on your phone or do you guys have a stereo, or what? … We just don’t have much of an idea about what day to day life is like for you guys. I mean, I guess we can imagine a little bit, but it’s hard to know really.’ The background becomes the foreground. Indeed, the very distinction falls away.

-

Desmond Manderson, Danse Macabre: Temporalities of Law in the Visual Arts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019). ↩

-

Mieke Bal, Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999); Georges Didi-Huberman, Before the Image, Before Time: The Sovereignty of Anachronism, trans. Peter Mason in Farago C and Zwijnenberg R Compelling Visuality: The Work of Art in and out of History (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003). ↩

-

This is a slight adaptation of a point made by Seth Kim-Cohen (2016: 58). He calls it a ‘dispute’ rather than a tension, but the point is the same. ↩

-

Both in the The Messenger and how are you today, Aziz went by his first name, as did all the other contributors to how are you today. This was a deliberate strategy of familiarisation and humanisation on their part in a context where refugees and asylum seekers are consistently otherised and even referred to by numbers. For that reason, we preserve the practice here. All other artists and authors are referred to by surname. ↩

-

Peter Chambers,‘Offshore Is a Form, Not a Place: Paradoxes, Global Spaces and Global Classes in Offshoring Finance and Detention,’ Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory 19/1 (2018): 1–27. ↩

-

Stephens Murdoch, ‘Manus Recording Project Collective: How Are You Now?’ City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi. https://citygallery.org.nz/blog/how-are-you-now/ ↩

-

Awards include the 2017 New York Festivals International Radio Awards: Grand Trophy winner, National and International Affairs Gold Medal and News Gold Medal; 2017 United Nations Association of Australia Media Peace Awards: Winner, Best Radio Documentary; 2017 Walkley Awards: Winner, Radio/Audio Feature; 2017 Australian Human Rights Commission Human Rights Awards: Winner, Media Award; 2017 Quill Awards: Finalist, Podcasting; 2018 Whickers Documentary Audio Recognition Award: runner-up. ↩

-

Maria Rae, Emma K Russell and Amy Nethery, ‘Earwitnessing Detention: Carceral Secrecy, Affecting Voices, and Political Listening in The Messenger Podcast,’ International Journal of Communication 13, (2019): 1038. ↩

-

Emily Ann Thompson, The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America, 1900–1933 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004); Tom Rice, ‘Sounds inside: prison, prisoners and acoustical agency,’ Sound Studies 2, (2016): 6-20; Carolyn McKay, The Pixelated Prisoner: Prison Video Links, Court ‘Appearance’ and the Justice Matrix, (Routledge, 2018); Maria Rae, Emma K Russell and Amy Nethery, ‘Earwitnessing Detention: Carceral Secrecy, Affecting Voices, and Political Listening in The Messenger Podcast,’ International Journal of Communication 13, (2019): 1036–55. ↩

This blurring of background and foreground is a dynamic that remains throughout the series. The voices of guards, of Aziz’s friends and fellow detainees, the sound of heavy rain on tin roofs, the compression and distortion that comes with contemporary digital telecommunication: when we listen to The Messenger, we never simply hear Aziz, but also the sounds of Manus and the conditions of our own listening. We listen to Aziz, but also with him, to and through WhatsApp. We always hear too much, more than was meant for us, and this ‘over-hearing’ feels like a kind of antidote to the ‘under-hearing’ deliberately manufactured by the Australian state. 1 A channel of sorts is opened, between offshore and on.

Eavesdropping

So much about The Messenger chimed with our thinking for a then nascent project called Eavesdropping. Eavesdropping was a lot of things. We ran reading groups, workshops, lecture series; we staged performances and produced a book. But at the project’s heart was an exhibition, shown first at the Ian Potter Museum of Art in Melbourne, in 2018, and then again at City Gallery Wellington, the following year. As a way of holding these various strands together, the term ‘eavesdropping’ was attractive to us — first, because of how immediately it gestured towards the ethical, legal, and political dimensions of listening, which in our view had been underrepresented curatorially;2 and, second, because of how enduring this association turned out to have been.

The earliest known references to eavesdropping are in court records. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first attested use of the noun ‘eavesdropper’ is from 1487 in the rolls of a local Sessions court in the Borough of Nottingham. But already in 1425, jurors in Harrow, Middlesex were reporting one John Rexheth for being a ‘common evesdroppere’, ‘listening at night and snooping into the secrets of his neighbors’.3 And in 1390, John Merygo, a chaplain in Norwich, was arrested for being ‘a common night-rover’, ‘wont to listen by night under his neighbour’s eaves’.4Eavesdropping, it seems, was one of the most commonly reported offenses in England’s market towns and rural villages all the way from the end of the 14th fourteenth century to the start of the sixteenth century.5 But the roots of the term are much older than that.6 And contemporary usage has long since exceeded eavesdropping’s medieval origins.

Today, eavesdropping refers to everything from the most inadvertent and trivial acts of overhearing through police wiretapping to global surveillance structures and the massive corporate data capture on which they depend. Much of this is perfectly legal. Despite eavesdropping’s origins as a language of censure and prohibition, its use in contemporary legal texts is often more ambivalent. Thus, s632 of the California Penal Code prohibits the intentional use of any ‘electronic amplifying or recording device to eavesdrop upon or record’ so-called ‘confidential communications’,7 only for s633 to immediately provide a blanket exception for law enforcement. Eavesdropping isn’t the problem here: only eavesdropping on certain communications (confidential)8, in a certain way (electronically), by certain people (private citizens).

Colloquially, eavesdropping retains its implication of transgression and so its critical edge. When we wield the term against major corporations like Apple or Amazon —‘Alexa has been eavesdropping on you this whole time’9 — the point isn’t that this kind of activity already is prohibited, but that it should be.10 Likewise, when we worry about neighbours or colleagues eavesdropping on us, when we close a door or don headphones in order not to overhear, it’s because we know some things aren’t meant for prying ears. All listening situations presume and imply a threshold of audibility. Eavesdropping is often the name given to this threshold’s breach.

What interested us about The Messenger, and what put it in conversation with many of the works we had already gathered or commissioned for the show, was the way it seemed to appropriate and valorise eavesdropping as a mode of activism, aesthetic production and critique.11 To begin with, listening to Aziz and Green’s messages, there is a sense of real intimacy, of ‘listening-in’ on a conversation never quite meant for you but to which you have nevertheless been granted an audience. ‘Eavesdropping with permission’, Tanja Dreher calls it,12 drawing on the work of Krista Ratcliffe.13 No doubt the intimacy and rapport between Aziz and Michael is crucial to the podcast’s success. But it is above all this sense of a threshold being breached, of ‘listening at a distance,’14 across physical and national boundaries, to and against forms of state brutality, that gives The Messenger its strongly political edge, and which also, therefore, makes it immediately legible as a work of legal advocacy. If silencing is a technique of power here, listening becomes a mode of resistance. The Messenger is very explicit about this, in fact. Not only does it enact a kind of eavesdropping, it frames it: directs us towards the politics of our listening, to the real risks taken by Aziz and Green in enabling it, and in doing so transforms us, perhaps, from eavesdroppers into earwitnesses, responsible now for what we’ve heard.15

Concept

Discussions for how are you today began in August 2017 when, based on our interest in The Messenger, we approached Green about taking part in Eavesdropping. Initially, we thought he and his collaborators might remix The Messenger archive, working with unheard or recontextualised messages, in an installation setting, but animating similar dynamics of listening. This approach wouldn’t impose anything on Aziz, we thought, whose ongoing detention we supposed made survival, not art, a priority. But the evolving situation on Manus led Green, Dao, and Tjhia — who had now officially come on board — to the opposite view. We didn’t want to use old messages, because the situation was ongoing — and besides, how could any exhibition treatment of the archival audio feel anything but exploitative? (But also: what alternatives were there?) Meanwhile, the weight of the detainees’ limbo grew heavier as the story lapsed from public attention. Yet, for the men on Manus, there was something new to respond to every day. We began to discuss inversions of a podcast, a project that allowed us to avoid selecting messages or shaping a narrative.16

Following a series of preliminary discussions in early 2018, in April we received the following proposal:

The idea now is to work with several men on Manus to record ten minutes of audio each day to play the next day in the gallery. The work would change everyday. This brings the listener into the present with the guys on Manus. They are still there, enduring. It is boring. Nothing is happening. Or maybe something will happen? Is a listener willing to stay with the men’s ongoing detention, or will they walk away? We won’t edit or mediate the recordings to create narrative or emotion as we did with the podcast, though likely we will work with each person in advance on what they may want to record, and how.17

Here, already, was an excellent summary of the work as it would eventually be realised.

By this stage, Green, Dao, and Tjhia had been in touch with a number of men on Manus with a view to participating in the project, including and via Aziz. The title how are you today was proposed: the most ordinary, but unavoidable, of questions; one that, in its various iterations, the team in Melbourne had found themselves asking time and again, and to which each audio recording would provide a provisional answer.18 The collaborating group, it was decided, would be called the Manus Recording Project Collective, an unwieldy name with the advantage of sharing an acronym with Manus Regional Processing Centre, where the men had first been brought together. The concept was finally proposed to the director and curators at the Ian Potter Museum of Art in late April 2018, two months before Eavesdropping opened.

Legalities

Right from this first proposal, how are you today generated more questions and curatorial challenges than any other work in the exhibition. Some we had anticipated. Ethically, of course, the work was complex. Would the demands entailed by its structure be too much for the artists? On whose behalf exactly were these demands being made? How to strike the balance between facilitating artistic expression under such extreme conditions and providing the men on Manus with adequate support and guidance in relation to the particular gallery context, especially since not all of them had worked as artists, or in this medium, before? What if either the content of a recording, or the process of recording itself, inadvertently exposed one of the men, or anyone else, to danger? What could we do to prevent that happening? And what would we do if we couldn’t? Likewise with the work’s audience. How to think about their possible exposure to the violence, self-harm, depression, suicide etc. that we knew pervades such spaces of detention? Practically, too, there were questions about how possible it would be to get recording equipment to Manus, how easy any such equipment would be to use, whether internet connections would be reliable enough to send high-fidelity recordings to Melbourne, and what would happen if the situation on Manus or for any individual artists changed suddenly during the course of the work. What kinds of practical, financial or other assistance could we provide? And how would any such eventualities be represented in the gallery? Politically, of course, we knew the work could prove controversial, and were prepared for a certain amount of dialogue about risk mitigation in this respect. But the specific ways in which these matters played out, along with the various other concerns tabled by the museum, came as a surprise. So many of the questions asked of how are you today were asked in the idiom of law. It was legal advice, ultimately, that would secure the work’s inclusion in the show and, it was hoped, on its own unique terms. And it was legal imaginations, often untethered from positive legal obligations or imperatives, that ended up governing key features of the work’s display … sometimes, it would turn out, in quite telling and productive ways.

Risk and Responsibility

Once how are you today had been approved in principle by the Ian Potter, conversations immediately began with Legal Services at the University of Melbourne about whether the work exposed the University to any ‘risk’, and if so whether this prevented it from being included.19 This process would ultimately yield a briefing paper on the work, which was understood as requiring and later received the Vice Chancellor’s approval, along with a modified loan agreement, the terms of which had been varied from the Museum’s boilerplate in a number of important ways.

Several matters were resolved quickly. Legal Services were clear, for instance, that the restriction on communications from Manus which had cast a shadow over the early phases of The Messenger and had been the subject of so much public controversy had now been removed, so that making and sending the recordings per se did not present a problem legally.20 Copyright in the recordings would reside with the individuals who had made them, and in the event that the recordings contained copyrighted material, such as music, this would be covered by the University’s licence agreement with APRA AMCOS. This was already a fudge, since the University would have no way of knowing or checking whether any such recording was from a ‘legitimate source’, as the licence required; or indeed whether it was included in the APRA AMCOS library. Perhaps this is why it ultimately sought to shift liability in this respect to us as curators, as we will see.

Ensuring that the men on Manus understood both the nature of the project and the rights, risks and obligations it entailed was more complex, but left largely to us to resolve. Dao, Green, and Tjhia produced, shared and explained a consent form with the men on Manus. The form covered permitted use of recordings, limitations of use, further consent, archiving the recordings, safety and privacy, and payment. It stipulated, for instance:

If you are recording someone speaking, make sure they know you are recording them, and what it will be used for. If possible, obtain oral consent from anyone you are recording, and include that consent in a separate file, sent to us along with the main recording. You must not endanger others through your participation in this project. If you feel your personal safety is being threatened due to your participation in the project, you must inform us and if necessary, stop recording. Your safety is our priority.21

Appropriately, consent was obtained in the form of voice-messages via WhatsApp. And this, Legal Services determined, was sufficient from the University’s perspective. Especially since the form also guaranteed the men ‘the ability to opt out at any stage and to require that their recordings be permanently destroyed at any time.’22

Concern regarding potentially traumatising, controversial, or generally unknown content in the recordings was more difficult to assuage and led to a more radical solution. Legal Services suggested that responsibility and, more important, liability, for how are you today be transferred from the Museum to us as curators. Where other works in Eavesdropping were loaned by artists directly to the Museum, how are you today would be loaned first to Liquid Architecture (‘The Curator’), the organisation at which Joel Stern was employed as Artistic Director, and only then to the Ian Potter Museum of Art. The terms of this arrangement were potentially extremely onerous. Liquid Architecture was asked to warrant, for instance, that ‘nothing in the work: (A) will breach any third party rights (including intellectual property or privacy rights); (B) is defamatory; (C) is misleading or deceptive; or (D) is otherwise unlawful.’ Moreover, Liquid Architecture would further indemnify the Museum ‘against all costs, losses or damages that may be incurred by the Ian Potter Museum of Art as a direct or indirect result of the Artist’s breach of its warranties.’23 Even then, the University remained concerned. Legal Services’ briefing paper insisted that ‘the University will not censor content’, but the following clause nevertheless made its way into the loan agreement:

a. The Curator will notify the Ian Potter Museum of Art if any controversial or sensitive content is present on individual Recordings of the Work, including content that may be defamatory, infringe third party rights, or contain sensitive information (including discussion of suicide or self-harm).

b. If necessary, the parties (in collaboration with the Producers) will:

(i) edit the Recording; or

(ii) take any other steps reasonably required, to address any controversial or sensitive information on the Recording, including displaying appropriate public warnings at the Exhibition.

c. The Ian Potter Museum of Art has the right to review and refuse to Use individual Recordings or parts of recordings, in its sole discretion (acting reasonably), if it is not satisfied that a remedy under clause 7(b) is satisfactory. 24

Not only did the University seek to offset all potential liability for how are you today onto us as curators, it wanted the ability to intervene in the work’s production, even where concerns over ‘sensitive information’ were raised in advance and attempts made by the artists to remedy them. True, in the exercise of this discretion, it was required to ‘act reasonably’, but what on earth that meant in this context or how this would all play out in practice was anybody’s guess.

In the event, the loan agreement was never actually sent through to Stern to sign. To this day we have no idea why, what we would have done had push come to shove, or indeed what the University imagined asking a cash-strapped arts organisation like Liquid Architecture to indemnify it against ‘all costs, losses or damages’ really amounted to in practice. As a result, the work’s legal status for the duration of its exhibition in Melbourne remains unclear. And, in the end, none of the eighty-four recordings eventually produced for how are you today was altered or even queried by the Museum. Nevertheless, it matters that this process was deemed essential for the work to proceed. Of course, the University’s nerves speak to some extent to the work’s uncertain nature: to the fact that it would unfold in real time, and that it did, therefore, present real risks. But in retrospect, it is hard not to suspect that the whole exercise was also something of a performance: for us, for the Vice Chancellor, and for an unknown future audience; that the University was concerned less with sculpting real obligations than appearing to have done its due diligence in the event of a complaint or public relations scandal. In this sense, the heavily improvised process also speaks to the general atmosphere in Australia around offshore detention in 2018: the climate of fear, secrecy, and rabid politicisation. Yes, the content of the ‘work’ was uncertain. But its context was what the University feared most, and it was this context to which the University was primarily responding with its (ultimately failed) attempt to contract out responsibility for a work which it nevertheless hosted and provided a platform for.

Terminology and Jurisdiction

This nervous dance between supporting how are you today and not wishing to take full responsibility for it played out again when it came to determining the appropriate language to describe the work and its participants. This time, however, the technique of disavowal was jurisdiction rather than contract.

At first, the Museum was concerned about the work’s art status: essentially that audio recordings from Manus may not, in and of themselves, constitute artworks, and that posing them as such risked aestheticising suffering and misrepresenting the status of the men on Manus, whose detention seemed at odds with the freedom and agency the title ‘artist’ would generally imply.

By 2018, field recordings had, of course, long lived in gallery settings, in pioneering works by Max Neuhaus, Hildergard Westerkamp, Bill Fontana, and countless others. These artists have a strong association with, indeed are progenitors of, ‘sound art’, experimental music, acoustic ecology, soundscape studies, and other sonic ‘genres’ with which Eavesdropping was centrally engaged.25 By now, all these genres have established conventions of listening widely understood by institutions and audiences. So, it is interesting that, for the Museum, the sense in which how are you today might belong to these historical modalities was initially illegible or opaque. Perhaps the men’s politicised status as refugees and prisoners overshadowed the work’s connection to these, by comparison, more prosaic sonic traditions; even though, of course, there are also long traditions of art being made from and about conditions of detention.26 Once it had been agreed that how are you today would, indeed, be ‘art’, we still had to fight to secure the men on Manus’ status as ‘artists’.

The Museum’s first suggestion was that, for the purposes of the loan agreement, ‘The Artists’ be listed as Dao, Tjhia, and Green in Melbourne, with the men on Manus acknowledged as (mere) ‘Participants’. This stemmed from a misunderstanding about the nature of the work, we said. The men on Manus were not going to simply ‘participate’ in the recordings, but ‘make’ them, whereas their Melbourne collaborators would facilitate, and, where necessary, provide the absolute minimum of editing. In the end, both in the loan agreement and in all public-facing accounts of the work, including in the gallery, all nine members of the collective were always presented as ‘artists’. But this was not the end of the terminological wrangling.

Similar questions arose again just days before the exhibition opened when it came to the didactic labels accompanying the work, and specifically how to represent the artists’ biographical details on the gallery’s walls. The standard designation in this respect was: place of birth; date; lives and works. For example: ‘Sean Dockray. Born Boston, United States 1977; lives and works in Melbourne’. But from a curatorial perspective, it was problematic to write, for instance: ‘Behrouz Boochani, born Ilam, Kurdistan 1983; lives and works on Manus Island’, without acknowledging the circumstances under which he lived and worked there. Our simple alternative was: ‘Behrouz Boochani, born Ilam, Kurdistan 1983; detained on Manus Island’. This, however, was rejected.

Some two years previously, on 26 April 2016, the Supreme Court of Papua New Guinea had ruled the detention of asylum seekers at the Manus Regional Processing Centre illegal on the grounds that it ‘offend[ed] against their rights and freedoms as guaranteed by the various conventions on human rights at international law’ and was contrary, moreover, to their Constitutional right of personal liberty as guaranteed by s42 of PNG’s Constitution.27 Thus began an interminable debate, widely aired in Australia but invariably mediated by the PNG courts, concerning whether and if so precisely when the centre had closed, when, accordingly, ‘detention’ there had ceased, and how to classify the new facilities to which the men were forced to relocate.

In March 2017, the PNG Supreme Court found that the 860 men still remaining were no longer strictly ‘detained’, on the basis that they were now ‘allowed to leave the centre during the day.’28 In a further decision from December 2017, following an application brought by ‘Behrouz Boochani and 730 others’, the court found that the actual date on which ‘detention’ had ceased was 12 May 2016.29 When the Manus Regional Processing Centre was finally emptied by force some eighteen months later, the six artists involved in how are you today were relocated to one of three centres on the island, named — with deliberate euphemism—West Lorengau Haus, Hillside Haus, and East Lorengau Transit Centre (ELTC).30 These facilities were guarded 24/7 and closed to the public. Asylum seekers were able to enter and exit only with a boat ID number and card. And in July 2018, a matter of weeks before Eavesdropping opened, a curfew was introduced preventing the men from leaving the centres between 6pm and 6am. At no point were they free to leave Manus without special permission from the PNG government. They may have been prisoners on day release, but they were prisoners all the same.

This was the backdrop against which the Museum worried that, for the purposes of how are you today’s didactic panel, it was inappropriate to describe the men as ‘detained’. We argued otherwise, pointing both to the men’s own accounts of their present conditions,31 and to the Refugee Council of Australia’s description of the new centres as a ‘heavily securitised environment … not open in the sense that anyone can come and go as they please, and access remains restricted even for human rights and humanitarian organisations.’32 But even as we did so, we were surprised and concerned that the Museum was so willing to defer, in their use of language, to legal institutions overseas and attempts by the Australian government to enforce such use at home.

-

Peter Szendy, All Ears: The Aesthetics of Espionage (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017); Brandon LaBelle, Sonic Agency: Sound and Emergent Forms of Resistance (London: Goldsmiths Press, 2018). ↩

-

For instance, in such major exhibitions as Sonic Boom (Hayward Gallery, London, 2000), Sound as a Medium of Art (ZKM | Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe, 2012), and Soundings: A Contemporary Score (Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2013). ↩

-

Marjorie Keniston McIntosh, Controlling Misbehavior in England, 1370–1600 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 65. ↩

-

Leet Roll of 14 Richard II (1390) in Seldon Society v 1892 (Leet Jurisdiction in Norwich). ↩

-

Marjorie Keniston McIntosh, Controlling Misbehavior in England, 1370–1600, 65. ↩

-

James E K Parker and Joel Stern, Eavesdropping: A Reader (Melbourne: City Gallery, 2019). ↩

-

California Penal Code 2020. ↩

-

Defined as ‘conversations where a party had no objectively reasonable expectation of being overheard or recorded’ in Chamberlain v Les Schwab (2012). ↩

-

Geoffrey A. Fowler, ‘Alexa Has Been Eavesdropping on You This Whole Time,’ The Washington Post, May 6, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2019/05/06/alexa-has-been-eavesdropping-you-this-whole-time/ ↩

-

The California State Assembly’s privacy committee has since proposed a new bill that would prohibit makers of smart speakers from saving or storing recordings without users’ explicit consent. Though the bill nowhere uses the word, it has nevertheless been dubbed the ‘Anti-Eavesdropping Act.’ ↩

-

The other artists involved were Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Susan Schuppli, Joel Spring, Sean Dockray, Samson Young, Fayen d’Evie and Jen Bervin. ↩

-

Tanja Dreher, ‘Eavesdropping with Permission: The Politics of Listening for Safer Speaking Spaces,’ Borderlands E-Journal 8/1, (2009): 1–21. ↩

-

Krista Ratcliffe, Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005). ↩

-

Peter Szendy, All Ears: The Aesthetics of Espionage (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017). ↩

-

Leah Bassel, The Politics of Listening: Possibilities and Challenges for Democratic Life (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017); Maria Rae, Emma K Russell and Amy Nethery, ‘Earwitnessing Detention: Carceral Secrecy, Affecting Voices, and Political Listening in The Messenger Podcast,’ International Journal of Communication 13, (2019): 1036–55. ↩

-

Manus Recording Project Collective, ‘how are you today’ in James E K Parker and Joel Stern, Eavesdropping: A Reader (Melbourne: City Gallery, 2019), 174. ↩

-

Michael Green, André Dao, and Jon Tjhia, email correspondence on file, April 20, 2018. ↩

-

André Dao, ‘How Are You Today” at the Ian Potter Museum of Art’ The Monthly, October 9, 2018. https://www.themonthly.com.au/blog/andr-dao/2018/09/2018/1539044312/how-are-you-today-ian-potter-museum-art#mtr ↩

-

University of Melbourne 2018a, Briefing paper, on file with authors. ↩

-

University of Melbourne 2018a. ↩

-

University of Melbourne, Manus Recording Project Collective ‘how are you today: Consent Form’, on file with authors, 2018b. ↩

-

University of Melbourne, Manus Recording Project Collective, 2018b. ↩

-

University of Melbourne, Loan Agreement, on file with authors, 2018c. ↩

-

University of Melbourne, 2018c. ↩

-

See, for instance: ‘Hildergard Westerkamp: Soundwork,’ Weber 2009, https://www.hildegardwesterkamp.ca/sound/; ‘Artist Statement,’ Bill Fontana https://www.resoundings.org. ↩

-

Nicole R Fleetwood, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2020). ↩

-

Namah v Pato (2016) SC1497: 67. ↩

-

Eric Tlozek, ‘PNG Chief Justice finds Manus Island Detention Centre Is Actually Closed’ ABC News, March 13, 2017. <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-03-13/ png-chief-justice-finds-manus-island-detention-centre-closed/8350600> ↩

-

Boochani v Independent State of Papua New Guinea [2017] SC1566. ↩

-

Amnesty International Australia and Refugee Council of Australia, Until When: The Forgotten Men of Manus Island, (Amnesty International Australia and Refugee Council of Australia, 2018).

<https://www. refugeecouncil.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Until_WhenAIA RCOA_FINAL.pdf> ↩ -

Ben Doherty, ‘Behrouz Boochani, Voice of Manus Island Refugees, Is Free in New Zealand,’ The Guardian, November 14, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/nov/14/behrouz-boochani-free-voice-manus-island-refugees-new-zealand-australia ↩

-

Amnesty International Australia and Refugee Council of Australia, 2018. ↩

Buildings at the East Lorengau Refugee Transit Centre and West Lorengau Haus on Manus Island. Photo: Australian Federal Government.

After initially being told we would have to settle for ‘lives and works’, which we deemed totally unacceptable from the perspective of curatorial ethics, we decided to play the Museum at its own game, and began looking for alternative wording in the various decisions of the PNG Supreme Court. This is how we came across the following passage from the Court’s 2016 decision declaring the Manus Regional Processing Centre illegal:

In the present case, the undisputed facts clearly reveal that the asylum seekers had no intention of entering and remaining in PNG. Their destination was and continues to be Australia. They did not enter PNG and do not remain in PNG on their own accord. This is confirmed by the very fact of their forceful transfer and continued detention on MIPC by the PNG and Australian Governments. Naturally, it follows that the forceful bringing into and detention of the asylum seekers on MIPC is unconstitutional and therefore illegal.1

This phrasing had been subsequently adopted by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and used in the opening lines of the ‘UNHCR Fact Sheet on Situation of Refugees and Asylum-seekers on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea.’2 The fact sheet states: ‘3,172 refugees and asylum-seekers have been forcibly transferred by Australia to facilities in Papua New Guinea and Nauru since the introduction of the current ‘offshore processing’ policy in 2013.’3

On that basis, we proposed the following description of the six artists on Manus:

Shamindan Kanapathi, born Colombo, Sri Lanka, 1990.

Samad Abdul, born Quetta, Pakistan, 1990.

Abdul Aziz Muhamat, born Geneina, Sudan, 1992.

Behrouz Boochani, born Ilam, Kurdistan, 1983. Farhad Bandesh, born Ilam, Kurdistan, 1981.

Hass Hassaballa, born Kutum, Sudan, 1988.4

Forcibly transferred from Australia to Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, where they remain.

Thankfully, this suggestion was accepted, and the artists have been described using similar wording in every in every iteration of the work since. The extraordinary result is that jurisdiction over the didactic labels for how are you today was doubly deferred to a foreign court: first, in ruling out the use of the word ‘detention’; second, in yielding another turn of phrase in its place — a turn of phrase which, in the end, was much more explicit both about the violence involved in delivering these six artists to Manus and, moreover, in implicating the Australian government. But notice that the Museum was under no obligation in this respect. The appeal to law was, once again, performative. The Supreme Court of PNG was deferred to not because it did have jurisdiction over the walls of a gallery in Melbourne, but as an act of disavowal in the event anyone asked questions. Take it up with the court, the Museum could now plausibly say. These are their words, not ours.

Preparation

As the exhibition drew nearer, the artists prepared for recording. Zoom H1 recorders were selected for use in the project since, in addition to being small, durable, and inconspicuous, when used effectively, they are capable of producing stereo recordings of broadcast quality. This upgraded the technology significantly from The Messenger, which had relied on the mobile phone microphone to which Aziz already had access on Manus. The higher-fidelity devices would enable subtler, quieter, and more complex sounds to be recorded.

Three Zoom H1s were delivered to Manus by an intermediary in July 2018. Instructions and recording tips were sent as a PDF via WhatsApp. In addition to their artist fees, the Manus artists were transferred extra money for the mobile data required to upload and transfer the files, and a technical infrastructure for how are you today playback was also developed. The six men on Manus would use WhatsApp or Telegram to send one recording each per week to their collaborators in Melbourne, who would then edit and mix the file and upload it to a Dropbox folder. In this respect, the three Melbourne artists would support two Manus artists each. This support involved receiving the recording, editing for duration and volume, and naming and transferring the file to the folder from which it would stream. But it was also creative, albeit that the guiding principle was to ‘intervene’ as little as possible. Preparatory conversations between Melbourne and Manus artists addressed questions of what to record and how. The following indicative transcript, for instance, is of an exchange between Kazem and Tjhia conducted two days prior to the exhibition opening:

Kazem, 22 July 2018

Voice-Messages

-

Namah v Pato (2016) SC1497: 37. ↩

-

UNHCR, UNHCR Fact Sheet on Situation Of Refugees and AsylumSeekers On Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, July 5, 2018a.

<https://www.unhcr.org/en-au/publications/legal/5b3ea38f7/unhcr-fact-sheet-on-situation-ofrefugees-and-asylum-seekers-on-manus-island.html?query=manus%20 island>. ↩ -

UNHCR, 2018a: 1. ↩

-

Hass Hassaballa subsequently dropped out of the project to be replaced by Kazem Kazemi, who was born in Ilam, Kurdistan in 1981. ↩

And, another topic is … that I want to, you know, work on it — cooking. I want to cook and record the voice of cooking, that I want to do. What do you think about that?

11.20 PM KazemAnd another one is — someone, you know, he just watching movies in his room, and nothing to do every day. And that’s another topic.

11.24 PM KazemAh, what about taking shower? I want to take shower, and record that. What do you think about that? Is it good or not?

11.25PM JonYeah! That sounds great too. I think … what is really good about these ideas that you have is that they sound pretty different, so you’ll produce a lot of stuff that opens up lots of different sides of life on Manus, and I think that’s great. Congratulations — these are very good ideas. (Manus Recording Project Collective 2019: 188)

Once a recording had been made, uploaded to Dropbox, and sent to Melbourne, the collaborators would produce a short descriptive title to be projected onto the wall of the gallery while it was playing. So, in relation to the above examples, which Kazem would go on to realise: on 6 September 2018, the title read, ‘Kazem, on Saturday, taking a shower’ and on 12 September 2018, ‘Kazem, on Monday, making a capsicum, mushroom and chicken pizza’.1

-

To listen to Kazem’s recordings, visit Manus Recording Project, https://manusrecordingproject.com. The same goes for each of the six other Manus artists. ↩

In the gallery, these titles did much to orient the listener, and signpost at least some of what they were hearing. As the work subsequently transformed into an archive and moved online, the titles grew in importance, becoming the index through which a listener might navigate from one recording to another. how are you today was installed at The Potter in a large rectangular gallery with a floorspace of approximately eight by twelve metres, and with five-metre-high ceilings. The walls of the gallery were painted charcoal black, and a single bulb in a parabolic lamp shade in the centre of the room provided the lighting. The sound system comprised four monitor speakers, angled inwards at forty-five degrees, suspended from the ceiling on drop poles. The four speakers formed a square of approximately three metres in the centre of the room. Twelve small white square stools arranged in four rows of three designated an ideal listening position. On one gallery wall, the work details were projected, featuring a timer counting from 00:00 to 10:00 minutes, the duration of each recording. Underneath, a wall-mounted iPad showed the title of what could be heard in the gallery that day, along with the growing list of prior recordings below.

While this image depicts a number of works in situ, it also gives a sense of the space in which how are you today was situated as part of Eavesdropping at Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne, Melbourne.

Manus Recording Project Collective, how are you today, 2018. Photo: Christian Capurro.

Manus Recording Project Collective, how are you today, 2018. Photo: Christian Capurro.

On 24 July 2018, the opening day of the exhibition, the first recording from Manus played in the gallery, ‘Aziz, last week, watching the World Cup final with the guys’. We hear the instantly recognisable sound of a stadium crowd played back through television speakers, and a commentator’s voice saying the word ‘Modric’. Then, the voices of a number of men, perhaps five or six, speaking quickly, excitedly, in Arabic. They chat, occasionally falling silent, perhaps in response to the game on screen. A few minutes pass, then rather suddenly ‘GOAL!’, shouting, laughing, a number of voices layering the soundscape. The recording continues, as the men continue to laugh and talk, before, at precisely ten minutes, the sound abruptly cuts. This was neither a narrative, nor an unadorned document, but something else. At no point did anyone acknowledge the microphone, or listener. As Dao puts it in the essay included in this collection:

I could hear the men speaking to each other but I couldn’t understand what they were saying. I didn’t know if they were talking about the game, which I knew was the World Cup Final between France and Croatia, a game that I myself had been watching at the very same time as the men in the recording. Perhaps they were talking about Manus, the Pacific island off the coast of Papua New Guinea where they have been detained for nearly five years. Perhaps they were talking about home, which I guessed — drawing upon what I already knew about Aziz, the man who had placed the microphone in the room in the middle of these voices — I guessed that for most of them home was Sudan. 1

On 24 August 2018, one month after the exhibition opened, a recording titled, ‘Behrouz, yesterday, speaking at Macquarie University via Whatsapp with his translator’ plays in the gallery. We hear Omid Tofighian, translator of Behrouz’s book No Friend But the Mountains,2 dialling in from Sydney, his voice filtered by the narrowband fidelity of the mobile phone. He is speaking Farsi. Behrouz is on the other end of the line, in Manus. Tofighian’s words are cutting in and out, distorted, glitching to the point of indecipherability. Behrouz listens patiently. There is a politics of fidelity at work here, in how ‘offshoring’ on Manus Island registers in the degraded quality of the audio signal. Communication becomes laborious and imprecise. The recording we hear, of course, is Behrouz’s. So, while Tofighian’s voice is distorted, the Manus soundscape in which it resounds is rich and clear. The multiple fidelities at work remind us that the medium of how are you today is not so much audio, but the offshore detention complex itself, and the desperate logic that structures it.3 A broken voice on a bad connection is one of the audible effects of the system that the work sets out to explore and expose.

-

André Dao, ‘What I Heard About Manus Island (When I Listened to 14 Hours of Recordings from Manus Island),’ Law Text Culture, Vol.24, (2020). ↩

-

Behrouz Boochani, No Friend But the Mountains (London: Picador, 2018). ↩

-

James E K Parker and Joel Stern, Eavesdropping: A Reader (Melbourne: City Gallery, 2019), 24. ↩

Behrouz, yesterday, speaking at Macquarie University via WhatsApp with his translator

On the same day that Behrouz and Omid speak (24 August, 2018), Scott Morrison deposes Malcolm Turnbull as Prime Minister of Australia, defeating Peter Dutton in an internal vote. Morrison and Dutton as former Immigration Ministers were co-architects of ‘Operation Sovereign Borders’, a policy that militarised Australian borders, based on rhetoric of ‘illegal arrivals’ and ‘illegal boats’. The new Prime Minister, Morrison, is pictured in his office with a trophy: ‘a laser-cut block of metal in the shape of an Asian fishing boat, sitting on a gently curving wave, with the thick black lettering: “I stopped these.”’1 Morrison, like Dutton, haunts the Manus recordings, although neither is referred to directly. Andrew Brooks notes as much in his reading of the work, when his listening reminds him of Morrison’s 2015 appearance on Annabel Crabb’s ABC television show, Kitchen Cabinet.2 Brooks describes watching ‘in disbelief as Morrison announced he would cook Crabb a Lankan meal of fish curry and samosas (which he nicknamed “ScoMosas”).3 His breezy appropriation of Lankan culture — my culture — was a ham-fisted attempt to prove that he is not racist.’ Contrast this with the how are you today recording, ‘Shamindan, last week, speaking with Srirangan while he cooks fish curry’ from 28 July 2018. In the sound of wind, scraping, and water running, we hear Sri Lankan Tamil refugee Shamindan Kanapathi interview another refugee making a fish curry. He begins preparing the meal in the laundry — there is no kitchen — before moving to the more confined space of a shared room. ‘Why do you cook?’ asks Shamindan. ‘I have been in this camp for more than five years. I am sick and tired. There is nothing else to do here. So I cook’, Srirangan answers. Returning to Kitchen Cabinet: ‘The inane kitchen chatter that Crabb and Morrison performed is the sound of patriarchal white sovereignty in action’, writes Brooks.4 His insight speaks to the capacity of the how are you today recordings to transform our listening ‘onshore’, to insist on co-locating the sounds of Manus and Australia.

-

Helen Davidson, ‘“I Stopped These”: Scott Morrison Keeps Migrant Boat Trophy in Office,’ The Guardian, September 19, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/sep/19/i-stopped-these-scott-morrison-keeps-migrant-boat-trophy-in-office ↩

-

ABC TV 2012-2018 Kitchen Cabinet. ↩

-

Andrew Brooks, ‘Listening to the Indefinite,’ Runway Journal, Vol. 41, (2018). <http://runway. org.au/listening-to-the-indefinite> ↩

-

Andrew Brooks, ‘Listening to the Indefinite’. ↩

Shamindan, last week, speaking with Srirangan while he cooks fish curry

The recordings that constitute how are you today are heterogeneous, varied, and diverse. As the work unfolded, one recording gave little indication as to what the following day’s would deliver. Recordings accumulated: the men making and listening to music; in the jungle; by the sea; cooking and cleaning; trying to relax; speaking with each other and locals. It became evident that what was being shared, in many instances, were not speech acts but ‘acts of listening’, characterised by a refusal to narrate, perhaps a refusal to reduce the experience of incarceration to a digestible story. The soundscapes reflected boredom, limbo, and time passing, without resolution or promise. Ten minutes spent listening reflected ten minutes spent recording. This sharing of time was powerful for the way it also made legible the twenty-three hours and fifty minutes of every day of incarceration that went unshared. The ‘everydayness’ of the recordings belied their specificity however. Behrouz’s contributions evidenced his increasingly intensive journalistic and writing activities with various publishers, translators, and collaborators. Aziz’s activism and advocacy is audible in a number of his recordings where he supports, organises, and rallies, both within the camp, and externally. Kazem’s and Farhad’s musical identities become clear, as they record themselves playing guitar, trumpet, and singing in various rooms at the facility. Samad and Shamindan started to develop highly idiosyncratic modes of address over time. ‘Hi everyone, it is Samad from Manus Detention Centre’, became a familiar opening. Shamindan’s ‘Dear brothers, dear sisters, dear friends’ felt likewise. Addressing the listener directly and intimately transforms them, in a sense, from eavesdroppers to earwitnesses, just like with The Messenger. We know you are listening, that you’ve heard, the men might have been saying; so what happens now?

how are you today at City Gallery, Wellington

Eavesdropping at The Potter ended on 28 October 2018, and so did how are you today as a live project. The final recording, ‘Samad, at three o’clock this morning, home from work and lying in bed, listening to music, is a goodbye note to listeners. Samad Abdul has relocated from Manus Island to Port Moresby over the course of the three months, and, in the recording, speaks hopefully of a day ‘when all of us will get out of jail in PNG … able to have our real lives, reunited with our families’. The recording ends with several minutes of Pakistani pop music played on small speakers in Samad’s room, against the whirring background noise of a fan as he tries to sleep.

Samad, at three o'clock this morning, home from work and lying in bed, listening to music

On 17 August 2019, how are you today opened at City Gallery in Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand for the next iteration of Eavesdropping. The period between closing in Melbourne and opening in Wellington had been eventful. In February 2019, Aziz had obtained a temporary visa to travel to Switzerland from Manus Island for the Martin Ennals Award for Human Rights Defenders. He had been nominated by Green on the basis of the activism so powerfully represented in the The Messenger. Aziz would win the award and go on to speak compellingly at The United Nations in Geneva, telling the world, ‘This award sheds light on the very cruel refugee policy of the Australian Government. It also brings international attention to the dangers and ill-treatment faced by refugees all over the world, including in countries that claim they uphold the Refugee Convention.’1 Aziz claimed asylum in Switzerland and was, after some months, accepted, becoming the first of the how are you today artists to leave Papua New Guinea.

Notwithstanding Aziz’s achievement, the political atmosphere was still unfavourable. In May 2019, Scott Morrison, against predictions, had been returned as Prime Minister, providing further mandate to his detention policies, among other things. Opposition leader Bill Shorten had stated ‘Australia would accept New Zealand’s offer to resettle some of the refugees on Manus Island and Nauru if Labor is elected,’2 but with his defeat, this promise was never tested. Morrison’s election provoked an atmosphere of despair on Manus. Behrouz described it as ‘out of control’, with suicide and self-harm spiking dramatically.3 As the Wellington exhibition opened, five of the six how are you today artists remained on Manus Island or Port Moresby, along with hundreds of other detainees.

The archive of recordings had now been compiled as an online collection, indexed chronologically and by artist.12 What was initially an open channel for listening in almost ‘real-time’ became an archive for listening-back on demand. While this online archive was important in terms of the project’s accessibility, especially for researchers, the ability to ‘surf’ from one recording to the next did not necessarily facilitate the kind of focused listening — this sense of sharing time or listening with the men on Manus, even across time and space — that we wanted to foster. So, at City Gallery, the work was presented in a cinema space with tiered seating for about 100 people, immediately adjacent to the rest of the exhibition. Played chronologically throughout the day, the full fourteen -hours took two days to complete. In that dark space, with high-quality speakers and cinema acoustics, it was possible to hear more in the sound than ever before. Yet, it was difficult to know what these sounds signified as an archive. Almost a year after they had been made, listening back to them was unsettling. In revisiting those sonic worlds, the difficulties of the time since were foregrounded: the dire situation of the men still in detention, the offer of resettlement from New Zealand rejected by the Australian Government. In June, two months before the Wellington exhibition, Behrouz spoke via Skype at Goldsmiths, University of London as part of a symposium called ‘Sound Proofs’.13 Over a poor, frequently glitching connection, he had said of how are you today:

We cannot change this generation. They are following what the government thinks. Unfortunately, this project, my work, and other peoples’ work, is only a record of history. It’s for the next generation … We have movies, we have books, we have this project, we have many materials. And these materials are important so that researchers are able to do research on the basis of this work, and all of the young generation are able to engage with this… [inaudible] I think we should accept that.4

Behrouz’s dignified resignation was a powerful prism through which to relisten to the archive, lending it the quality of an acoustic ethnography, a future researcher’s tool for understanding the sound of Australian offshore detention circa 2018. In the beauty and sadness of the recordings, a hidden functionality was coming to the surface, a sense of the recordings as something else, also important: evidence, against the forces of erasure and forgetting.

Concluding / Introducing

In this essay, we have attempted to account for how are you today by the Manus Recording Project Collective, foregrounding not only the recordings, but also the curatorial ethics that attended their production, the institutional negotiations that became necessary at different moments, and the shifting political contexts, legal processes, and imaginations that shaped the project. It is in considering these elements together, we argue, that ‘the work’ is most legible and its meaning most fully realised. Reflecting on how are you today in a review of the first iteration of Eavesdropping for The Wire, Philip Brophy (2019) wrote:

Most field recordings are sonically boring — not to mention patronising in their supposed raising of consciousness by listening to the outside world. Revealingly, they demonstrate an entitled sense of freedom, as if the world is yours to openly record. how are you today stridently reverses these entitled notions: the detainees are excessively restricted spatially, yet sonically they are still capable of uncovering micro sound worlds through their individual site-specific acts of listening.5

How to listen for and with this lack of freedom, as Brophy suggests? Only by tuning-in — turning one’s ears — to context: to information beyond the ‘frame’ of the recordings ‘themselves’; to details that, though not sonically ‘present’, radically alter both the experience of listening and the meaning of the work.

Once the door has been opened to what Seth Kim-Cohen, riffing on Marcel Duchamp, calls the ‘non-cochlear dimensions’ of the work, they quickly saturate it. ‘The normally supplemental parerga’, KimCohen writes, borrowing Derrida’s term,6 ‘become central to the act of encounter’. ‘Contexts impose themselves: past experiences, future expectations, adjacent sounds, other works, institutional settings, curatorial framing. All these influences, and other parerga besides, are essential components of our experience of what we call “the work.”’7 Even if they can’t be ‘heard’. In order to explore and appreciate these dimensions of the work, Kim-Cohen claims — indeed of any encounter with the sounding world — we must move beyond a concern for sound-in-itself, beyond vibration, beyond even the ‘jurisdiction of the ear,’8 towards sound’s necessary social-embeddedness.

This is the kind of encounter with how are you today we have been arguing for, and that we think the work also presumes and demands. As a form of listening, it is, in a way, ‘excessive’. It invites the listener to hear ‘too much’: more than was meant for them, more than is even ‘there’, ‘in’ the recordings. Listening this way involves the breach of a threshold, therefore. This is also a kind of eavesdropping, whereby the listener permits themselves — since it cannot, after all, be avoided — to over-hear: not only the sounds of Manus and the men forced and held there, not only evidence of all this against the geographic, political, and legal forces that would rather none of this was heard, but also something of the strange ways in which these forces play out in curatorial and Uuniversity contexts, as mediated by improvised legal processes and rampant legal imaginations, and how, in the process of becoming archival, whether heard online or in a gallery in New Zealand, the recordings are animated anew by interminable stasis, contemporary political events and even, occasionally, by hope.

On 14 November, 2019, to the amazement of millions, Behrouz Boochani landed in Aotearoa New Zealand, having left Papua New Guinea more than six years — 2,269 days — on from his forcible transfer there by the Australian Government. This was a shock to all but a small group who had been working over a number of months to arrange the transfer. The UNHCR had provided travel documents to leave Papua New Guinea, Amnesty International had sponsored the visa, and Word Christchurch, a small literary festival, had nominated itself as his New Zealand host.9

This is how it came to be that on 17 November, 2019, the final day of Eavesdropping at City Gallery, the exhibition had a surprise visitor. Behrouz toured the show, meeting with curators and other artists in the exhibition, before addressing a large audience in the same cinema space where how are you today had been playing for the previous three months. He spoke about each of the other five men; where they are now, in Port Moresby, in Australia under the so-called ‘Medevac Bill’10 and Aziz, in Switzerland. And, incredibly, he was in a position to listen, in the gallery, as a free person, to the recordings that he and his friends had made a little over a year earlier, from a place of seemingly indefinite incarceration.

Two weeks later, Behrouz would speak again at the 2019 meeting of the Law, Literature and Humanities Association of Australasia, on Yugambeh land in the Gold Coast. The conversation, which was conducted by André Dao, covered Boochani’s journey to New Zealand, his time on Manus, his journalism, book and films, but was principally concerned with how are you today: his experience making the work, the motivations behind particular recordings, his reflections a year later. A lightly edited transcript follows this piece. After that comes Dao’s own essay,11 in which he listens in detail to the work’s first seven recordings, but from the specific vantage point of an artist involved in the work’s production and who has also listened through the entire archive; which, at fourteen hours, is no mean feat (this, indeed, is how Dao’s essay gets its title). Dao’s essay is about these recordings, but also about the experience of listening to them: a hearing, a re-hearing and also, in a way, a pre-hearing, he explains. What we read is Dao ‘listening to himself listening’;12 noticing the different forms of knowledge, ignorance, pathos, attention, sorrow and surprise that structure his encounter with the recordings. ‘As a staged hearing’, Dao writes, ‘the essay itself gestures to another meaning of the word —– to the trial or the scene of judgment. Which is not to say that the hearer in this case has the authority of the judge. To be clear: nothing in this hearing can alter the material circumstances of the six men making the recordings.’ Not just that. Despite the archive’s status as ‘evidence’ of a sort, it is not an experience that admits a simple normative response of the kind a lawyer might listen out for. That, for Dao, may be its virtue. He ends by asking with Simone Weil what it would mean to listen to something like how are you today not in the register of ‘rights’ but ‘justice’: which is to say precisely not as a lawyer; without ‘instrumental ears’; despite and against Dao’s own legal training. The mute justice of a hearing without a verdict.

The next two essays are by thinkers who weren’t involved in the production of the work. Like Dao, Poppy de Souza also develops her essay through individual recordings. Like Dao, she is also interested in how, despite failing to conform to any ‘recognisable genre of refugee testimony’ or narrating any particular injustice, indeed precisely because it ‘confounds expectations of what life in an offshore ‘“black site”’ might sound like’, it seems to have been ‘forged of, and might help forge, more just relations of attention.’ Crucially though, for de Souza, if how are you today suggests or entails a certain justice, this is not a matter of empathy, compassion, or even understanding, since these can all tend towards the depoliticization of systemic issues. Rather, she explains, how are you today points us towards ‘the more difficult, durational and justice-oriented listening needed to unsettle Australia’s settler colonial border regimes.’ ‘Taken together, or heard collectively,’ she argues, ‘the work invites us to listen beyond the horizon of the state in order to hear the enduring-ness of life on Manus — the solitude and suffering, but also the sociality and solidarity — as well as the limits of what settler colonial carceral logic and law can hear.’

For Emma Russell, the issue is less the limits of carceral logic than the production of ‘carceral atmospheres’, a term she coins to help think through how are you today. A carceral atmosphere, she says, is both the ‘product and effect of technologies of confinement —– those disciplinary mechanisms of law, power, and surveillance that detrimentally keep in and contain bodies within space and time.’ how are you today both conveys and creates such atmospheres, Russell explains, and in doing so ‘provides models for denaturalising detention through creative practices of transborder solidarity.’

Through the accumulation of ‘everyday’ soundworlds, it seeks to create a space for intimate and uncomfortable engagement with the repetitive and often mundane reality of life in enforced limbo. Through eschewing sensationalism and dramatic violence, it prompts us to question the reactionary frame of ‘crisis’ that dominates liberal refugee politics in Australia and instead attune to the ‘‘slow violence’’ of abandonment at the border.

This is a violence in which time itself is weaponised, where ‘hotels and homes can be repurposed as prisons’, and where the experience of carcerality, though undoubtedly material, is also profoundly sensory, which is to say ‘permeable and unstable’, felt as much as seen. But as Russell points out, how are you today isn’t just an archive of atmospheres, but of acts of resistance: both in itself, as an artwork, and in the moments it records, like when we hear Aziz speaking from Manus at a protest in Melbourne. ‘By capturing these daily practices of resistance,’ Russell contends, ‘how are you today provides an historical record of collaborative, cross-border campaigning against the secretive and unaccountable system of offshore detention.’

So much has changed since this essay was first drafted at the start of 2020. Back then, Behrouz’s future in New Zealand was still unclear. His initial one-month visa had lapsed and Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern had stated that any further developments were ‘totally hypothetical.’13 Behrouz, for his part, had said of Papua New Guinea and Australian detention: ‘I will never go back to that place.’14 Then in July 2020, almost seven years to the day after he was arrested by the Australian Navy, taken to Christmas Island, and subsequently flown to PNG, the New Zealand government finally granted him asylum. He is now a Senior Adjunct Research Fellow at the University of Canterbury. ‘I look at it as an end of chapter of my life and I feel happy because I have certainty for my future’, Boochani told the ABC. ‘But on the other side it’s extremely difficult because still this policy exists and still people are living in detention in Australia, in Port Moresby and Nauru and still the Australian Government continues with this policy of torturing people.’15 So much remains the same.