- 33EMYBW

Shanghai native 33EMYBW (Wu Shanmin) has been an active member in the Chinese music scene for over a decade. She has also performed at CTM and Sinotronics in Germany, China Drifting Festival in Switzerland, and SXSW. Her 2018 album Golem, released on SVBKVLT, was met with critical acclaim and voted one of the best electronic albums of 2018 by Bandcamp. In 2019 she released DONG2 EP under Merrie Records Beijing, and will premiere her sophomore album Arthropods (SVBKVLT) at Unsound 2019.

- Aasma Tulika

Aasma Tulika is an artist based in Delhi. Her practice locates technological infrastructures as sites to unpack how power embeds, affects, and moves narrative making processes. Her work engages with moments that disturb belief systems through assemblages of video, zines, interactive text, writings and sound. Aasma was a fellow at the Home Workspace Program 2019-20, Ashkal Alwan, her work has appeared in Restricted Fixations, Abr_circle, Khoj Art+Science program, HH Art Space. She is a member of the collective -out-of-line-, and collaboratively maintains a home server hosting an internet radio station. She is currently teaching at Ambedkar University Delhi.

- A Hanley

A Hanley is an artist currently living on Wurundjeri Country in Melbourne, Australia. Their practice uses sound and media to explore relations among queer ecologies, attunement, situatedness, and speculative practices. Engaging forms of performance, installation, and collaboration, Hanley's work is interested in audition as an affective practice and the possibilities of sound and technology to support and alter the sonic expressions of humans and non-humans.

- Aisyah Aaqil Sumito

Aisyah Aaqil Sumito is an artist and writer living near Derbarl Yerrigan on Whadjuk Noongar Bibbulmun lands. Their work reflects mostly on personal intersections of disability, queerness and diasporic ancestry in so-called 'australia'. They have recently made text-based contributions to Runway Journal and HERE&NOW20: Perfectly Queer, Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery.

- Alessandro Bosetti

Alessandro Bosetti is an Italian composer, performer and sound artist, currently based in Marseille. His work delves into the musicality of spoken language, utilising misunderstandings, translations and interviews as compositional tools. His works for voice and electronics blur the line between electro-acoustic composition, aural writing and performance.

- Alexander Garsden

Alexander Garsden is a Melbourne-based composer, guitarist and electroacoustic musician, working across multiple exploratory musical disciplines. Recent work includes commissions from the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, Speak Percussion, Michael Kieran Harvey and Eugene Ughetti; alongside performances with artists including Tetuzi Akiyama (Japan), Oren Ambarchi, Radu Malfatti (Austria), Julia Reidy, David Stackenäs (Sweden), and with Erkki Veltheim and Rohan Drape. From 2014 to 2019 Garsden was Co-Director of the INLAND Concert Series. He has taught through RMIT University and the University of Melbourne.

- Alexander Powers

Alexander Powers is a choreographer, performer and DJ from Naarm. In 2019 they premiered their first full length choreographic work Time Loop at the Melbourne Fringe Festival, receiving the Temperance Hall Award at the Fringe Awards. Under the moniker Female Wizard, they are known internationally for their forward-thinking DJ sets. They’ve performed at Golden Plains, Dark Mofo, Boiler Room, Hybrid Festival and Soft Centre and held a four year residency at Le Fag.

- Alexandra Spence

Alexandra Spence is a sound artist and musician living on unceded Wangal land in Sydney, Australia. Through her practice Alex attempts to reimagine the intricate relationships between the listener, the object, and the surrounding environment as a kind of communion or conversation. Her aesthetic favours field recordings, analogue technologies and object interventions. Alex has presented her art and music in Australia, Asia, Europe, and North America including BBC Radio; Ausland, Berlin; Café Oto, London; EMS, Stockholm; Punkt Festival, Kristiansand; Standards Studio, Milan; AB Salon, Brussels; Radiophrenia, Glasgow; Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid; Sound Forms Festival, Hong Kong; MONO, Brisbane; The Substation, Melbourne; Soft Centre, and Liveworks Festival, Sydney.

- Allanah Stewart

Allanah Stewart is an artist from Aotearoa/New Zealand, currently living in Melbourne, Australia. As well as her work in various experimental music projects, she is the presenter of a monthly podcast radio programme called Enquiring Minds, hosted by Noods radio, which explores old and new, lesser known and well known sounds that loosely fit under the banner of experimental music.

- Allison Gibbs

Allison Gibbs is an artist living and working on Djaara Country/Maldon, Victoria. She is currently a PhD candidate at Monash University Art, Design and Architecture (MADA).

Mouth Making an Orifice has been adapted for OOO/LA from a part of Allison’s doctoral research (Orificing as Method).

- Amanda Stewart

Amanda Stewart is a poet, author, and vocal artist. She has created a diverse range of publications, performances, film and radio productions in Australia, Europe, Japan, and the USA, working in literature, new music, broadcasting, theatre, dance, and new media environments. Amanda collaborated with Chris Mann for many years in the Australian ensemble, Machine For Making Sense (with Jim Denley, Rik Rue, and Stevie Wishart), as well as in other contexts. Her poem ‘ta’ was written in honour of Chris Mann’s extraordinary vision and work.

- Amy Cimini

Amy Cimini is a musicologist, violist, and Associate Professor of Music at UC San Diego. She works on questions of power, community, and technology in twentieth & twenty-first century experimental music, sound art, and auditory culture. She is the author of Wild Sound: Maryanne Amacher and the Tenses of Audible Life (OUP 2022) and numerous articles. She embraces feminist historiographic methods and, as a musician, centers performance-based epistemologies to query how culture workers negotiate power and difference within local, regional, and transnational histories.

- Anabelle Lacroix

Anabelle Lacroix is a French-Australian curator, writer and radio contributor. Working independently in Paris, she is based at Fondation Fiminco for a year-long residency focused on the politics of sleeplessness (2020). She has a broad practice, and a current interest in experimental practice, working with performance, sound, discourse and publishing. She is a PhD candidate at UNSW Art & Design.

- Ander Rennick

Ander Rennick is a graphic artist based in Melbourne interested in the fetishisation of editorial, pedagogical, pornographic and mimetic commodities.

- Andrew Brooks

Andrew Brooks is an artist, writer, and teacher who lives on unceded Wangal land. He is a lecturer in media cultures at UNSW, one half of the critical art collective Snack Syndicate, and a member of the Rosa Press Collective. Homework, a book of essays co-written with Astrid Lorange, was recently published by Discipline.

- Andrew Fedorovitch

Andrew Fedorovitch is compos mentis.

Andrew Fedorovitch embodies professionalism in every aspect of his life, including music.

- André Dao

André Dao is a writer, editor, researcher, and artist. His debut novel, Anam, won the 2021 Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for an Unpublished Manuscript. He is also the co-founder of Behind the Wire, an oral history project documenting people’s experience of immigration detention and a producer of the Walkley-award winning podcast, The Messenger. He is a member of the Manus Recording Project Collective.

- Ange Goh

Angela Goh is a dancer and choreographer. Her work poses possibilities for disruption and transformation inside the aesthetics and conditions of technocapitalism, planetarity, and the post-anthropocene. She lives and works in Sydney, and has toured her work across Australia, Europe, the UK, the USA and Asia. She received the 2020 Keir Choreographic Award and the inaugural Sydney Dance Company Beyond the Studio Fellowship 2020-21.

- Anna Annicchiarico

Anna Annicchiarico has a bachelor's degree in Hindi language and literature and she specialised in anthropology at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. For her studies, she focused on the effects of orientalism in post-colonial imageries, especially on migrants in Italy, analysing religious places, and their meaning for different generations. In recent years, she has been increasingly involved in contemporary art and performance.

- Anna Liebzeit

Anna Liebzeit composes for collaborations across installation, theatre, and film. Recent compositions include the feature film The Survival of Kindness (Rolf de Heer 2022), Sleeplessness Carriageworks (Karen Therese 2022), The Darkness of Enlightenment Samstag Museum of Art (James Tylor 2021), kipli pawuta lumi MONA FOMA (2020), and SHIT and LOVE by Dee and Cornelius (45 Downstairs, Venice Biennale 2019, and feature film SHIT 2021). Anna has made music for various NAIDOC events and has had work shown at various venues nationally.

Her solo practice investigates erasure and becoming inscribed, as a personal and broader (Australian) cultural phenomenon. Her research is linked to the lived experience of Stolen Generations and relationality by drawing on Susan Dion’s educative provocation to complicate empathy when engaging with First Nations peoples. Anna has been an educator in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and education for over twenty years and is an award-winning curriculum writer. In 2021 she received the Creative Victoria Creators Fund grant to research the intersections of her teaching and creative methodologies.

- Anne Zeitz

Anne Zeitz is associate professor at University Rennes 2. Her research focuses on aural attention, the inaudible, the unheard, and the polyphony in contemporary art. She directed the research project 'Sound Unheard' and she co-organised the eponymous exhibition at the Goethe-Institut Paris, Paris and exhibition 'Échos magnétiques” at the MBA Rennes, Rennes in 2019.

- Annika Kristensen

Annika Kristensen is Senior Curator at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne.

- Arben Dzika

Arben Dzika is an artist whose practice involves working with various media including, but not limited to: sound, image, word, and performance. His work primarily seeks to reflect on, interrogate, and play with technologies, systems, and human senses. Within his practice, he works as a producer and DJ under the moniker, Dilae.

- Archie Barry

Archie Barry is an interdisciplinary visual artist working with a trans politics of quietude. Their practice is autobiographical, somatic, and process-led, and spans performance, video, music production, and writing. Cultivating a genealogy of personas, they produce self-portraiture that brings to question dominant notions of personhood and representation.

- Arlie Alizzi

Arlie Alizzi is a Yugambeh writer living between Yawuru Country (Broome) and Wurundjeri Country (Melbourne). He is an editor, writer and researcher. He was an editor for Un Magazine with Neika Lehman in 2018, and co-edited a special issue of Archer Magazine in 2020. He was a writer-in-residence for MPavilion in 2019, and is interested in articulations of place in writing about urban areas.

- Arturo Escobar

Arturo Escobar is a Colombian American anthropologist and professor emeritus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His academic research interests include political ecology, anthropology of development, social movements, anti-globalization movements, political ontology, and post development theory. He is the author of Encountering Development (1995) and Designs for the Pluriverse (2018). His book Territories of Difference: Place, Movements, Life, Redes, analyses the politics of difference enacted by specific place-based ethnic and environmental movements in the context of neoliberal globalisation, drawing on years of fieldwork in Colombia with a group of Afro-Colombian activists of Colombia's Pacific rainforest region called the Proceso de Comunidades Negras (PCN).

- Audrey Jo Pfister

Audrey Jo Pfister is a writer, editor, curator, and adjunct DJ based in Naarm/Melbourne originally from Dharawal/Wollongong. Audrey is the General Manager at the arts publisher, un Projects, occasional creative producer for SOFT CENTRE, and full-time fan of many things.

- Audrey Schmidt

Audrey Schmidt is a writer and editor based in Melbourne, Australia. She is a regular contributor to Memo Review, co-editor the third issue of Dissect Journal, and has written for various publications including Art Monthly, Art + Australia and un Magazine. She co-founded Minority Report with Adam Hammad in 2018 and released one online issue that was available until the domain expired in 2019. Audrey sits on the FYTA (GR) Board of Advisors.

- Aura Satz

Aura Satz is a London-based artist based who works with film, sound, performance and sculpture. Her works explore a distributed, expanded and shared notion of voice, and are made in conversation, using dialogue as both method and subject matter. Satz has made several film portraits of listening and compositional practices as well as works centred on sound technology and unusual notation systems. ‘Preemptive Listening’ is her first feature film, with support from artist residencies at Walker Arts Centre and EMPAC, funded by an AHRC fellowship hosted at the Royal College of Art.

- Austin Benjamin

Austin Benjamin, known for his stage name Utility, is a Sydney-based music producer, artist & founder of the label Trackwork. He’s released projects through Room 40, Sumac, HellosQuare, and produced music for releases on labels including Universal NZ, AVTV, Warner & 66 Records. In 2019 Utility & close collaborator T. Morimoto released Nexus Destiny featuring a collection of 60 arpeggios made entirely with software synthesisers, released on Melbourne-based label Sumac.

Earlier this year Utility performed alongside T Breezy, Walkerboy, Sevy & Bayang at Sydney Opera House’s Barrbuwari event. Austin has previously composed and performed new works for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, and University of Queensland Art Museum with T. Morimoto, and MONA FOMA Tasmania with turntablist Martin Ng and has exhibited audio-visual gallery works including ‘Strategic Innovation’ with Coen Young at Kronenberg Wright, Sydney.

- Autumn Royal

Autumn Royal creates drama, poetry and criticism. Autumn is the founding editor of Disclaimer journal and interviews editor at Cordite Poetry Review. Autumn’s current research examines elegiac expression in contemporary poetry

- Beatriz García-Velasco

Beatriz García-Velasco is Assistant Curator, International Art at Tate Modern. She works for a range of projects spanning exhibitions, live performances, commissions and the Tate Film programme, and develops the Tate collection through the Latin American Acquisition Committee. Recent projects include the Mike Kelley: Ghost & Spirit and the Capturing the Moment exhibitions; the Noémie Goudal: ANIMA and Pan Daijing: Tissues and The Absent Hour performances; the Preemptive Listening symposium; and Cecilia Vicuña’s Brain Forest Quipu Hyundai commission. Before her time at Tate Modern, Beatriz worked at the Contemporary British Art Department at Tate Britain and the Publishing Department at the Museo Nacional del Prado.

- Beau Lai

Beau Lai (formerly Lilly) is an artist and writer currently based in Paris, France. Beau spent their formative years working intensively within the contemporary arts industry on Darug and Gadigal land in so-called 'Australia'. They are most well known for self-publishing their essay and work of institutional critique, 'Working at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. It does not exist in a vacuum', in 2020.

- Behrouz Boochani

Behrouz Boochani is a Kurdish-Iranian writer, journalist, scholar, cultural advocate and filmmaker. He was writer for the Kurdish language magazine Werya. He writes regularly for The Guardian and several other publications. Boochani is also co-director (with Arash Kamali Sarvestani) of the 2017 feature-length film Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time, and author of No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison. He was held on Manus Island from 2013 until 2019.

- Ben Raynor

Ben Raynor is an artist, living in Melbourne.

- Bianca Winataputri

Bianca Winataputri is a Melbourne-based independent curator and writer researching contemporary practice in Southeast Asia, and relationships between individuals and collectives in relation to history, globalisation, identity and community building. Currently working at Regional Arts Victoria, Bianca was previously Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art at the NGA. She holds a BA (University of Melbourne), and BA Honours from the ANU where she received the Janet Wilkie Prize for Art. In 2018 Bianca was selected for 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art’s Curators’ Intensive.

- Bola Chinelo

Bola Chinelo is a multimedia artist based in Los Angeles. Chinelo’s work uses esoteric symbolism, coding languages, and sonic and iconographic languages to convey messaging.

- Brad Darkson

Brad Darkson is a South Australian visual artist currently working across various media including carving, sound, sculpture, multimedia installation, and painting. Darkson's practice is regularly focused on site specific works, and connections between contemporary and traditional cultural practice, language and lore. His current research interests include traditional land management practices, bureaucracy, seaweed, and the neo-capitalist hellhole we're all forced to exist within. Conceptually, Darkson's work is often informed by his First Nations and Anglo Australian heritage. Brad's mob on his dad's side is the Chester family, with lineages to Narungga and many other Nations in South Australia from Ngarrindjeri to Far West Coast. On his mum's side he is from the Colley and Ball convict and settler migrant families, both arriving in 1839, aboard the Duchess of Northumberland.

- Brandon LaBelle

Brandon LaBelle is an artist, writer and theorist working with sound culture, voice, and questions of agency. Guided by situated and collaborative methodologies, he develops and presents artistic projects and performances within a range of international contexts, mostly working in public and with others. This leads to performative installations, poetic theater, storytelling, and research actions aimed at forms of experimental community making, as well as extra-institutional initiatives, including The Listening Biennial and Academy (2021-ongoing). From gestures of intimacy and listening to critical festivity and experimental pedagogy, his practice aligns itself with a politics and poetics of radical hospitality.

- Brian Hioe

Brian Hioe was one of the founding editors of New Bloom, an online magazine covering activism and youth politics in Taiwan and the Asia Pacific, founded in 2014 in the wake of the Sunflower Movement. Hioe is a freelance writer on social movements and politics, as well as an occasional translator.

- Bridget Chappell

Bridget Chappell is a writer and artist. She produces and DJs under the name Hextape.

- Bryan Phillips

Bryan Phillips A.K.A. Galambo is a Chilean/Australian artist working in community arts, music and performance, using sound as a means to facilitate engagement with others. His practice has mainly been developed in Chile, but after completing his Masters in Community Cultural Development (VCA-2013) he has become involved in projects with artists from Timor-Leste, Indonesia and Australia.

- Camila Marambio

Camila Marambio is a private investigator, amateur dancer, permaculture enthusiast, and sporadic writer, but first and foremost, she is a curator and the founder/director of Ensayos, a nomadic interdisciplinary research program in Tierra del Fuego.

- Camille Norment

Camille Norment is an Oslo-based multimedia artist who works with sound, installation, sculpture, drawing, performance, and video. Norment also works as a musician and composer. She performs with Vegar Vårdal and Håvard Skaset in the Camille Norment Trio. In 2015, she represented Norway in the Nordic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Additionally, Norment has completed several commissioned works to public spaces, amongst others the sound installation "Within the Toll" (2011) for Henie Onstad Kunstsenter and her 2008 work "Triplight," which in 2013 was featured at the entrance of the MoMA exhibition "Soundings: A Contemporary Score."

- Candice Hopkins

Candice Hopkins is a curator, writer and researcher interested in history, art and indigeneity, and their intersections. Originally from Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, Hopkins is a citizen of Carcross/Tagish First Nation. She was senior curator for the 2019 Toronto Biennial of Art, and worked on the curatorial teams for the Canadian Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, and documenta 14.

- Carina Fearnley

Carina Fearnley is Professor of Warnings and Science Communication at the Department of Science and Technology Studies, UCL, and Director and Founder of the UCL Warning Research Centre (WRC), the only such dedicated facility in the world. Carina is an interdisciplinary researcher, drawing on relevant expertise in the social sciences on scientific uncertainty, risk, and complexity to focus on how natural hazard early warning systems can be made more effective, specifically alert level systems. As a world leading authority on warning and alert level systems Carina established the World Organisation of Volcano Observatories Volcano Alert Level Working Group, and edited the first publication dedicated to Volcanic Crisis Communication, and more recently the 7th edition of the textbook Environmental Hazards.

- Casey (Nicholls-Bull) Jones

Casey (Nicholls-Bull) Jones is the assistant editor for Liquid Architecture's Disclaimer.

She is also an artist who utilises embodied knowledge, plant and herbal study, research, and deep listening as the backbones of her practice. Through unhurried and repetitive processes such as pyrographic wood burning techniques, oil painting, and the observation of and connection to natural cycles and materials, Jones uses these methods to rearrange, layer, peel back, and continually connect to knowledges, memories and histories that are personally felt, encountered, and observed around her. Jones uses the moon cycle as a continual framework to maintain the rhythm and logic of her practise, and is continually in the midst of deconstructing the complexity of working as a settler on unceded Wurundjeri land through her processes of both making and understanding. Her hope is that through circling, living through, and re-curringly interrogating these things she studies and tends to, something fruitful may gradually become embodied, communicated and understood in new ways by herself and those who encounter her work.

- Casey Rice

Sound Mastering: Casey Rice is an audio doula living and practicing on Djaara Country/Castlemaine, Victoria.

- Catherine Ryan

Catherine Ryan is an artist who works with performance, sound, text, video and installation. She often uses humour and references to philosophical and pop figures to interrogate the neoliberal disciplining the body. She has exhibited at galleries and festivals in Australia and Europe, including Gertrude Contemporary, MUMA (Melbourne), the Royal College of Art (London), the Vienna Biennale and the Melbourne Art Fair. She is currently a PhD candidate at RMIT University, researching how ideas from experimental composition, cybernetics and performance can help us wrestle with the existential threat of extinction that climate change and other catastrophes pose to life on our planet.

- Cecilia Vicuña

Cecilia Vicuña's work dwells in the not yet, the future potential of the unformed, where sound, weaving, and language interact to create new meanings.

'In January 1966, I began creating precarios (precarious) installations and basuritas, objects composed of debris, structures that disappear, along with quipus and other weaving metaphors. I called these works 'Arte Precario', creating a new independent category, a non-colonized name for them. The precarios soon evolved into collective rituals and oral performances based on dissonant sound and the shamanic voice. The fluid, multi-dimensional quality of these works allowed them to exist in many media and languages at once. Created in and for the moment, they reflect ancient spiritual technologies—a knowledge of the power of individual and communal intention to heal us and the earth.'

—Cecilia Vicuña

- Cher Tan

Cher Tan is an essayist and critic living and working on unceded Wurundjeri Country. Her work has appeared in the Sydney Review of Books, Hyperallergic, Runway Journal, Art Guide Australia, Catapult and Overland, amongst others. She is an editor at LIMINAL and the books editor at Meanjin. Her debut essay collection, Peripathetic: Notes on (Un)belonging, is forthcoming with NewSouth Publishing in 2024.

- Chi Tran

Chi Tran is a writer, editor, and an artist who makes poems that may be text, video, object, sound, or drawing. Chi is primarily interested in working with language as a means of coming-to-terms. Their work has been published by Incendium Radical Library Press, Cordite Poetry Review, Australian Poetry and Liminal Magazine and exhibited at galleries including Firstdraft, Sydney; Punk Café, Melbourne; and ACCA, Melbourne. In 2019, as a recipient of The Ian Potter Cultural Trust Fund, Chi spent three months in New York developing their practice with renowned poets including Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Fred Moten, and Jackie Wang.

- Christopher LG Hill

Christopher L G Hill is an artist, poet, anarchist, collaborator, facilitator, lover, friend, DJ, performer, sound pervader, publisher of Endless Lonely Planet, co-label boss; Bunyip trax, traveller, homebody, dancer, considerate participator, dishwasher, writer, bencher, eater, exhibitor: Sydney, Physics Room, Westspace, TCB, BUS, Punk Cafe,100 Grand street, Lismore Regional Gallery, Good Press, Gambia Castle, Conical, GCAS, NGV, VCA, Mission Comics, Slopes, Art Beat, Papakura Gallery, Neon Parc, UQ Gallery, Tate Modern, Connors Connors, Glasgow International, Sandy Brown, OFLUXO, New Scenarios, Margaret Lawrence, Flake, Utopian Slumps, World Food Books, Sutton, Rearview, Joint Hassles, a basement, a tree, Innen publications, SAM, Chateau 2F, etc, and tweeter, twitcher, sleeper, Biennale director (‘Melbourne Artist initiated’ 2008, 2011, 2013, 2016, 2018-20), DJ, retired gallerist Y3K, conversationalist who represents them self and others, born Melbourne/Narrm 1980c.e, lives World.

http://www.christopherlghill.com/

https://twitter.com/CLGHill

https://www.instagram.com/christopherlghill/

https://bunyiptrax.bandcamp.com/

https://jahjahsphinx.blogspot.com/

https://boobasprite.tumblr.com/

http://counterfeitnessfirst.blogspot.com/

http://newtabandwindowshopper.blogspot.com/

https://www.mixcloud.com/Christopher_L_G_Hill/

http://anotheryouapictureavoicemessagemime.blogspot.com/

- Chun Yin Rainbow Chan

Chun Yin Rainbow Chan is a Hong Kong–Australian artist, living in Sydney. Working across music, performance and installation, Rainbow is interested in the copy and how the ways in which it can disrupt Western notions of ownership. Central to Rainbow's work is the circulation of knock-off objects, sounds and images in global media. Her work positions the counterfeit as a complex sign that shapes new myths, values and contemporary commodity production.

- Claire G. Coleman

Claire G Coleman is a Noongar writer, born in Western Australia, and now based in Naarm. Her family have been from the area around Ravensthorpe and Hopetoun on the south coast of WA since before time started being recorded. Claire wrote her black&write! Fellowship-winning book Terra Nullius while travelling around Australia in a caravan. The Old Lie (2019) was her second novel and in 2021 her acclaimed non-fiction book, Lies, Damned Lies was published by Ultimo Press. Enclave is her third novel. Since mid 2020 Claire has also been a member of the cultural advisory committee for Agency, a Not-for-profit Indigenous arts Consultancy.

- Clare Cooper

Clare M. Cooper has brought together thousands of people to work together on community festivals, skill-share spaces, pleasure activism, speculative design, and critical listening through co-founding the NOW now (2001), Splinter Orchestra (2000), Berlin Splitter Orchester (2009), Frontyard Projects (2016), and Climate Strike Workshop (2019).

She wrote her PhD thesis on the intersections of context-responsive improvised music practice and collaborative design, and is a Lecturer at the University of Sydney School of Design Architecture and Planning. Disclaimer journal's profile on Cooper, written by Jim Denley can be found here.

- Clare Milledge

Clare Milledge is an artist and academic, she lives and works between the lands of the Arakwal people in Bundjalung country (Broken Head, Northern NSW) and the lands of the Bidjigal and Gadigal people (Paddington, Sydney). She is a Senior Lecturer at UNSW Art & Design and is represented by STATION gallery.

- Coco Klockner

Coco Klockner is an artist and writer living in New York City. Recent exhibitions include venues such as The Alfred Ceramic Art Museum, Alfred, NY; Interstate Projects, Brooklyn; Guadalajara90210, CDMX; The Luminary, St. Louis; Bass & Reiner, San Francisco; Lubov, New York; ONE Archives, Los Angeles; and Egret Egress, Toronto. They are the author of the book K-Y (Genderfail, 2019) and have published writing with Montez Press, Real Life Magazine, Spike Art Magazine, and Burnaway.

- Dale Gorfinkel

Dale Gorfinkel is a musician-artist whose stylefree improvisational approach informs his performances, instrument-building, and kinetic sound installations. Aiming to reflect an awareness of the dynamic nature of culture and the value of listening as a mode of knowing people and places, Dale is interested in bringing creative communities together and shifting perceived boundaries. Current projects include Prophets, Sounds Like Movement, and Music Yared as well as facilitating Art Day South, an inclusive arts studio with Arts Access Victoria.

- Dame Evelyn Glennie

Dame Evelyn Glennie (OBE, CH) is the world’s premier solo percussionist. Her solo recordings exceed 40 CDs. Curator of The Evelyn Glennie Collection, Evelyn composes for film, theatre and television, launching The Evelyn Glennie Podcast in 2020. Her film Touch the Sound, TED Talk and charity The Evelyn Glennie Foundation embody her life-long mission to Teach the World to Listen. “My career and my life have been about listening in the deepest possible sense. Losing my hearing meant learning how to listen differently, to discover features of sound I hadn’t realised existed. Losing my hearing made me a better listener.”

- Damiano Bertoli

Damiano Bertoli was an artist and writer who worked across drawing, theatre, video, prints, installation and sculpture. With works of great humour and intelligence, Bertoli was best known for his ongoing series Continuous Moment, which sprawled a range of mediums across multiple works, ultimately circulating on time itself. His practice gravitated toward aesthetic and cultural moments, particularly related to his birth year of 1969.

- Daniel Green

Daniel Green is an artist and performer. His practice explores the objects and media we use to occupy our time, and how they are used to give our lives meaning. Daniel’s work has been exhibited within Campbelltown Arts Centre, Pelt, Artspace and BUS Projects, and has performed at Electrofringe, The Now Now Festival, Liquid Architecture, the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, and Cafe OTO in London. He lives and works in London.

- Daniel Jenatsch

Daniel Jenatsch makes interdisciplinary works that explore the interstices between affect and information. His work combines hyper-detailed soundscapes, music and video to create multimedia documentaries, installations, radio pieces, and performances. He is the winner of the 2020 John Fries award. His works have been presented in exhibitions and programs at ACCA, UNSW, Arts House, Kunstenfestivaldesarts, the Athens Biennale, NextWave Festival, Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Liquid Architecture Festival, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, and the MousonTurm, Frankfurt.

- Danni Zuvela

Danni Zuvela is a curator and writer based in Melbourne and the Gold Coast. Her research is informed by interests in feminism, activism, ecology, language and performance. With Joel Stern, Danni has led Liquid Architecture as Artistic Director, and continues to develop curatorial projects for the organisation.

- David Toop

David Toop has been developing a practice that crosses boundaries of sound, listening, music and materials since 1970. This encompasses improvised music performance, writing, electronic sound, field recording, exhibition curating, sound art installations and opera. Briefly a member of David Cunningham’s pop project The Flying Lizards in 1979, he has released fourteen solo albums and published eight acclaimed books. His 1978 Amazonas recordings of Yanomami shamanism and ritual were released on Sub Rosa as Lost Shadows (2016). Curator of sound art exhibitions including Sonic Boom at the Hayward Gallery (2000), his opera – Star-shaped Biscuit – was performed in 2012.

- Debris Facility

Debris Facility Pty Ltd is a para-corporate entity who engages im/material contexts with the view to highlight and disrupt administrative forms and their embedded power relations. Deploying print, design, installation, and wearables as the most visible parts of operations, they also work in experimental pedagogy and perforated performance of labour. They are a white-settler parasite with theft and dispossession as the implicated ground from which they work. They currently hold contracts with Liquid Architecture, Victorian College of the Arts, Monash University and Debris Facility Pty Ltd.

- Denise Helene Sumi

Denise Helene Sumi is art historian, author and professionally involved in culture.

- Diego Ramirez

Diego Ramirez makes art, writes about culture, and labours in the arts. In 2018, he showed his video work in a solo screening by ACCA x ACMI and he performed in Lifenessless at West Space x Gertrude Contemporary in 2019. His work has been shown locally and internationally at MARS Gallery, ACMI, Westspace, Torrance Art Museum, Hong-Gah Museum, Careof Milan, Buxton Cotntemporary, WRO Media Art Biennale, Human Resources LA, Art Central HK, Sydney Contemporary, and Deslave. His words feature in Art and Australia, NECSUS, un Projects, Runway Journal, Art Collector, and Australian Book Review. He is represented by MARS Gallery, Editor-at-large at Running Dog and Gallery Manager at SEVENTH.

- Dimitri Troaditis

Dimitri Troaditis works in the Greek-Australian media. As a poet he has been extensively published in Greece and in Australia in numerous literary journals, websites, blogs and anthologies. He has published six poetry collections and two social history books so far. He has organised poetry readings in Melbourne for years and translates others’ poetry. He runs poetry website To Koskino and was a resident of Coburg for 19 years.

- Douglas Kahn

Douglas Kahn is an historian and theorist of energies in the arts, sound in the arts and sound studies, and media arts, from the late-nineteenth century to the present. He lives on unceded Dharug and Gundungurra land. His books include Energies in the Arts (MIT Press, 2019); Earth Sound Earth Signal: Energies and Earth Magnitude in the Arts (University of California Press, 2013); Noise Water Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts (MIT Press, 1999); Mainframe Experimentalism: Early Computing and the Foundations of Digital Arts, edited with Hannah Higgins (University of California Press, 2012); and Source: Music of the Avant-garde, edited with Larry Austin (University of California Press, 2011).

- Dr. Lawrence Abu Hamdan

Dr. Lawrence Abu Hamdan

Internationally Known Private Ear

Serving Industries of Culture Since 2007

Licensed & Bonded: Goldsmiths College, University of London

Civil | Criminal | Human | Marital | Theological | Supernatural

Bureaus: Beirut, Berlin, Dubai, London

- Dylan Martorell

Dylan Martorell is an artist and musician based in Narrm/Melbourne Victoria. He is a founding member of Slow Art Collective, Snawklor, Hi God People, and Forum of Sensory Motion. He has performed and exhibited internationally, including projects with; Art Dubai, Asian Art Biennale, Tarrawarra Biennale, Jakarta Biennale and Kochi Muzirus Biennale. His work often combines site-specific materiality and music to create temporary sites for improvised community engagement.

- Dylan Robinson

Dylan Robinson is a xwélméxw (Stó:lō) writer, artist, scholar and curator, He is Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Arts, and associate professor at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. He is author of Hungry Listening, Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies, published by University of Minnesota Press.

- Elaine Mitchener

Elaine Mitchener is a vocalist, movement artist and composer working between contemporary, experimental new music, free improvisation and the visual arts. She is currently a Wigmore Hall Associate Artist; was a DAAD Artist-in-Berlin Fellow (2022) and was an exhibiting artist in the British Art Show 9 (2021-22). Elaine is founder of the collective electroacoustic unit The Rolling Calf (with Jason Yarde and Neil Charles). While developing her own projects, Elaine continues to work as a collaborative and interpretive singer.

- Elena Biserna

Elena Biserna is a scholar and independent curator based in Marseille (France), working at the intersection of social, political and public spheres.

- Eloise Sweetman

Eloise Sweetman loves art, misses her home in Western Australia, all the time loving Rotterdam where she became friends with Pris Roos whose artwork Sweetman speaks of. Sweetman is a curator, artist, writer and teacher working in intimacy, not knowing and material relation. She started Shimmer with Dutch-Australian artist Jason Hendrik Hansma in 2017.

- Emile Frankel

Author of Hearing the Cloud (Zero Books), Emile Frankel is a writer and composer researching the changing conditions of online listening. In his spare time he runs the science fiction and critical fantasy publisher Formling.

- Emma Nixon

Curious about the tender intersections between art, life and friendships, Emma Nixon is an emerging curator and writer. In 2018 she completed a Bachelor of Art History and Curating at Monash University and co-founded Cathedral Cabinet ARI in the Nicholas Building. In Melbourne she has curated and written about exhibitions that investigate subjects such as abstraction, the domestic, care and collage within contemporary art.

- Emma Ramsay

Emma Ramsay is active across experimental dance and DIY music; sound performance; and other text collaborations. She works in community media and archives.

- Emma Russell

Emma Russell is a critical carceral studies scholar and senior lecturer in crime, justice and legal studies at La Trobe University, Australia. She researches and writes on policing and criminalisation, prisons, detention, and activism. Emma is the author of Queer Histories and the Politics of Policing (2020) and co-author of Resisting Carceral Violence: Women’s Imprisonment and the Politics of Abolition (2018).

- Eric Avery

Eric Avery is a Ngiyampaa, Yuin, Bandjalang and Gumbangirr artist. As part of his practice Eric plays the violin, dances and composes music. Working with his family’s custodial songs he seeks to revive and continue on an age old legacy – continuing the tradition of singing in his tribe – utilising his talents to combine and create an experience of his peoples culture.

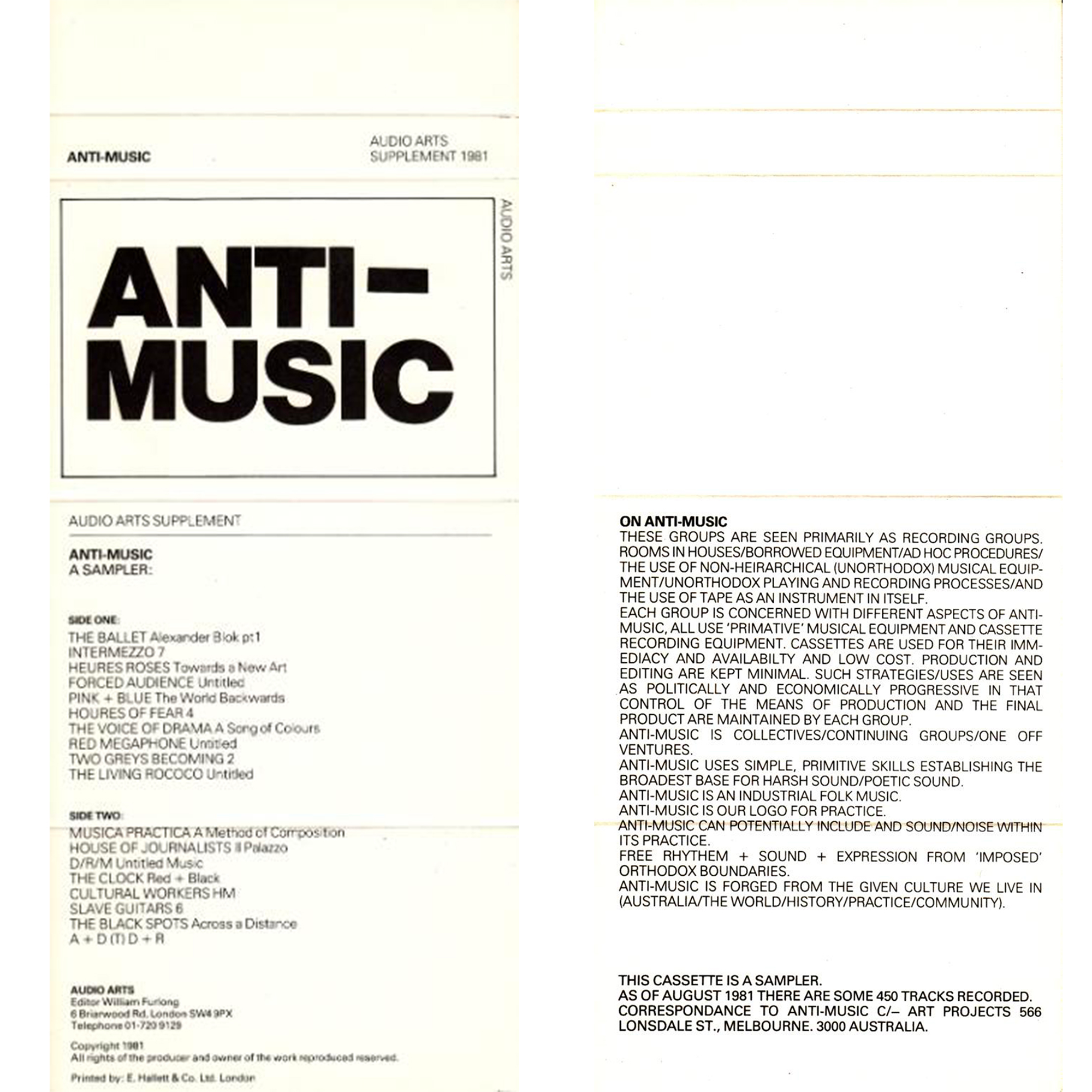

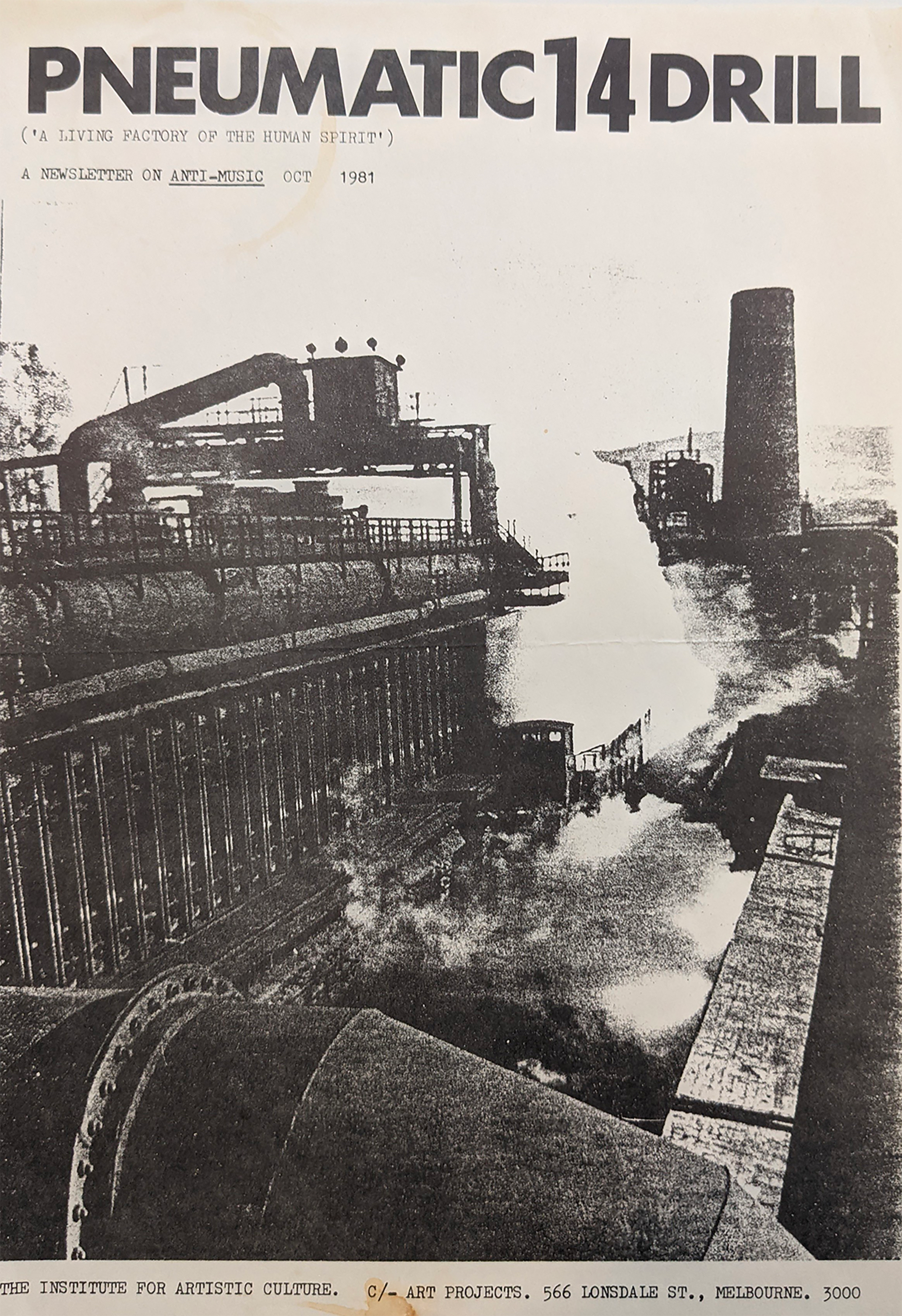

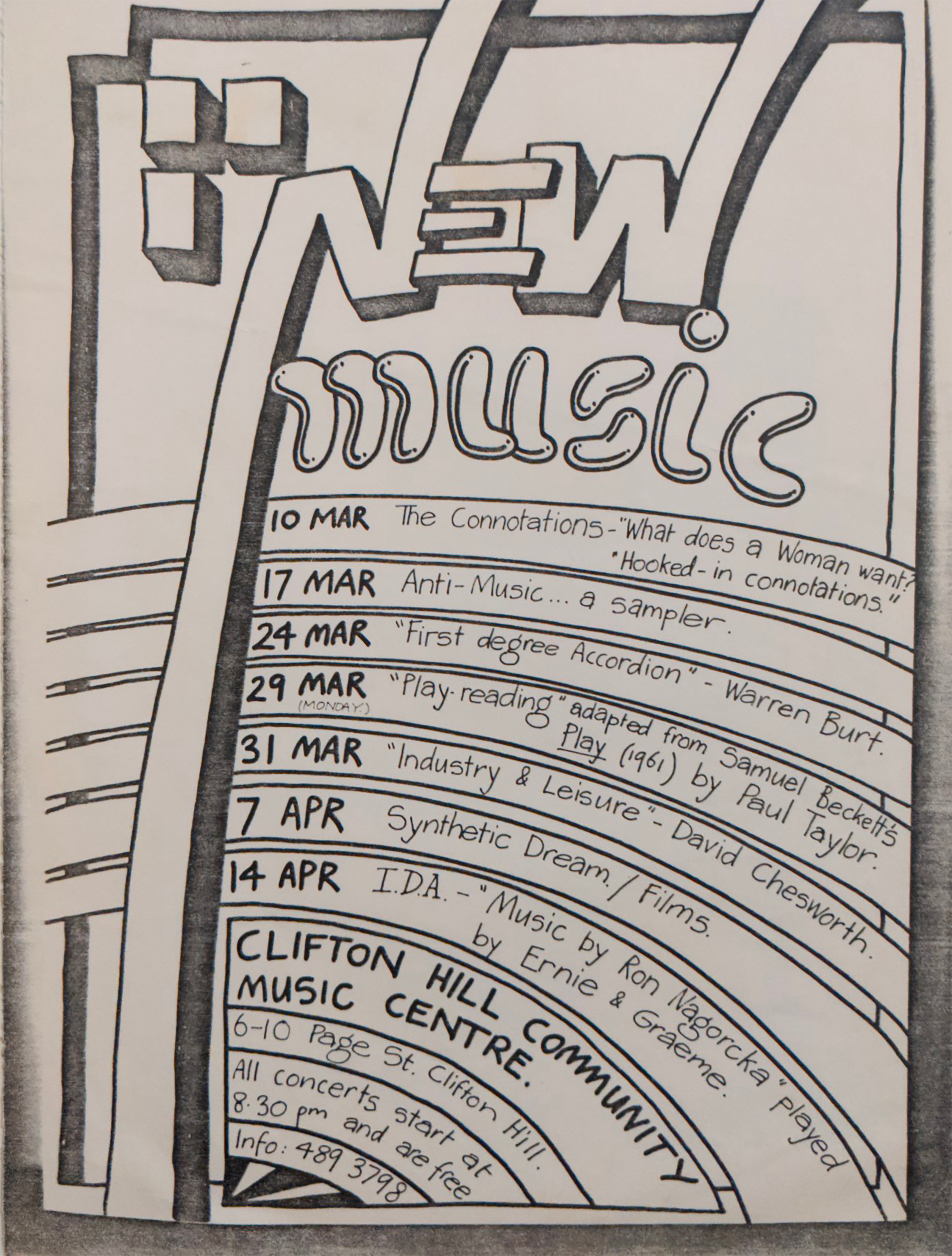

- Ernie Althoff

- Ernie Altohff

Ernie Althoff has been making experimental music since the late 1970s, and is well-known for his work. Throughout this period he has always remained true to his exploratory ideals.

- Evelyn Glennie

Dame Evelyn Glennie (OBE, CH) is the world’s premier solo percussionist. Her solo recordings exceed 40 CDs. Curator of The Evelyn Glennie Collection, Evelyn composes for film, theatre and television, launching The Evelyn Glennie Podcast in 2020. Her film Touch the Sound, TED Talk and charity The Evelyn Glennie Foundation embody her life-long mission to Teach the World to Listen. “My career and my life have been about listening in the deepest possible sense. Losing my hearing meant learning how to listen differently, to discover features of sound I hadn’t realised existed. Losing my hearing made me a better listener.”

- Fayen d'Evie

Fayen d’Evie is an artist and writer, based in Muckleford, Australia. Her projects are often conversational and collaborative, and resist spectatorship by inviting audiences into sensorial readings of artworks. Fayen advocates the radical potential for blindness, arguing that blindness offers critical positions and methods attuned to sensory translations, ephemerality, the tangible and the intangible, concealment, uncertainty, the precarious, and the invisible. With artist Katie West, Fayen co-founded the Museum Incognita, which revisits neglected or obscured histories through scores that activate embodied readings. Fayen is also the founder of 3-ply, which investigates artist-led publishing as an experimental site for the creation, dispersal, translation, and archiving of texts.

- Fileona Dkhar

Fileona Dkhar is an Indigenous Khasi visual artist based in Rotterdam, Netherlands, and Shillong, India. Her work entwines the personal with mythology and history as storytelling devices.

- Fjorn Butler

Fjorn Bastos is an artist, researcher, and event organiser. As an artist, she works primarily in sound and performance under the name Papaphilia. As a researcher, she interrogates how biological discourses are used in neoliberal/colonial governance structures to shape the political. Fjorn's research informs her writing on sound-poetics and the challenges this framework poses to anglophone notions of property. She is also co-director of Future Tense and co-curator of Writing and Concepts.

- Frances Barrett

Frances Barrett is an artist who lives and works on Kaurna land in Tarntanya/Adelaide. Frances is currently Lecturer in Contemporary Art at University of South Australia.

- Francesca Laura Cavallo

Francesca Laura Cavallo is a curator, art historian, and interdisciplinary researcher whose work focuses on the intersection between art and the activation, management, and perception of risk. She is a Research Associate and a Lecturer at the Royal College of Arts in London and is writing a book on the Aesthetics of Risk (Palgrave McMillan, 2025). Her work has been presented in museums and institutions such as Wellcome HUB, Tate Modern, British Museum, Barbican, Science and Industry Museum, Turner Contemporary, Manifesta 11, the ICA, MACRO Rome and the Museo Zoque Regional in Chiapas Mexico. She was an AHRC Research Associate on Preemptive Listening.

- Francis Carmody

Francis Carmody’s artistic practice serves as a useful alibi to reach out to people he admires across disciplines and technical capabilities to share stories and complete projects. Through tracing networks and natural structures, he would like to get to the bottom of what the hell is going on.

This process of enquiry draws on meticulous research, cold calling, persistence and frequent rejection. Creating an ever-expanding list of Project Partners.

- Francis Plagne

Francis Plagne is a musician and writer. He has written about contemporary art for major Australian publications and institutions. His writing on music and sound art has appeared in Disclaimer and as liner notes to several releases on Black Truffle. Inspired by prog, MPB, free jazz and the poetry of John Ashbery and Clark Coolidge, his music fragments and extends song form into unexpected shapes, crossing over into group improvisation, instrumental miniatures, and domestic musique concrète. He has been performing regularly since 2005 and has released recordings on labels such as Black Truffle, Horn of Plenty, Kye Records, Penultimate Press and his own Mould Museum micro-label. He teaches Art History at the University of Melbourne.

- Freya Schack-Arnott

Freya Schack-Arnott is an Australian/Danish cellist who enjoys a multi-faceted career as a soloist and ensemble performer of classical and contemporary repertoire, curator and improviser within experimental music, electronics, popular and cross-disciplinary art forms. Schack-Arnott regularly performs with Australia's leading new music ensembles, including ELISION Ensemble (as core member) and Ensemble Offspring. Her curatorial roles include co-curator/founder of the regular 'Opus Now' music series and previous curator of the NOW Now festival and Rosenberg Museum.

- Gail Priest

- Geoff Robinson

Geoff Robinson is a Melbourne-based artist working on Wurundjeri country. Robinson creates event-based artworks that utilise the temporal qualities of sound and performance and the spatial conditions of physical sites to unravel the durational layers of place. Robinson has presented projects with Titanik, Turku; Bus Projects, Melbourne; Liquid Architecture, Melbourne; and MoKS, Mooste, Estonia. He was awarded the Melbourne Prize for Urban Sculpture 2014 and completed the PhD project Durational Situation at MADA, Monash University, Melbourne, 2018.

- Georgia Hutchison

Georgia Hutchison is a cultural development practitioner and arts executive in Naarm/Melbourne, and Executive Director/CEO of Liquid Architecture. Her practice as an artist, educator, organiser and strategist crosses contemporary art, music, design and social justice.

- Giselle Au-Nhien Nguyen

Giselle Au-Nhien Nguyen is a Vietnamese-Australian writer, journalist and critic based in Naarm/Melbourne. Her work has been published widely in media and literary publications including The Age, The Guardian, Meanjin and Sydney Review of Books.

- Gooooose

Gooooose (Han Han) is an electronic music producer, visual artist and software developer based in Shanghai, China. His current releases include They (D Force, 2017), Dong 1 (D Force, 2018), Pro Rata (ANTE-RASA, 2019). Gooooose's 2019 SVBKVLT–released RUSTED SILICON received positive reviews from media including boomkat, Resident Advisor, Dusted Magazine, and The Wire. Gooooose has performed live at CTM (Berlin, 2018), Nyege Nyege (Kampala, 2019), Soft Centre (Sydney, 2019), Unsound (Kraków, 2019) and Recombinant (San Francisco, 2019).

- Hannan Jones

Hannan Jones is an artist working at the intersections of sound, installation, performance and moving image.

- Han Reardon-Smith

Han Reardon-Smith (they/them) is a white settler of Welsh and Turkish heritage and is a musicker, radio/podcast producer, community organiser, and thinker-scholar.

- Harmony Holiday

Harmony Holiday is a writer, dancer, archivist, director, and the author of four collections of poetry, Negro League Baseball, Go Find Your Father/A Famous Blues, Hollywood Forever, and A Jazz Funeral for Uncle Tom. She lives in New York and Los Angeles.

- Haroon Mirza

Haroon Mirza is an artist who intertwines his practice with the role of composer. Mirza considers electricity his main medium and creates atmospheric environments through the linking together of light, sound, music, videos and elements of architecture. Regularly showing internationally in group and solo exhibitions, Mirza’s work has also been included in the 7th Shenzhen Sculpture Biennale, China (2012) and the 54th Venice Biennale, Italy (2011), where he was awarded the Silver Lion.

- Hillel Schwartz

Hillel Schwartz is a cultural historian, poet, and translator. Schwartz has been both a fellow at and an adviser to the Millennium Institute, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit organization founded in the 1980s to work on global sustainability issues. Books include The Culture of the Copy Striking Likenesses, Unreasonable Facsimiles; Long Days, Last Days: A Down-to-Earth Guide for Those at the Bedside; Making Noise: From Babel to the Big Bang and Beyond. He is currently writing a book on the cultural history of Emergency.

- Holly Childs

Holly Childs is an artist and writer. Her research involves filtering stories of computation through frames of ecology, earth, memory, poetry, and light. She is the author of two books: No Limit (Hologram, Melbourne) and Danklands (Arcadia Missa, London), and she collaborates with Gediminas Žygus on ‘Hydrangea’. She is currently writing her third book, What Causes Flowers Not to Bloom?.

- Holly Herndon

Holly Herndon experiments at the outer reaches of dance music and pop. Born in Tennessee, Herndon spent her formative years in Berlin’s techno scene and repatriated to San Francisco, where she completed her PhD at Stanford’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics. Her albums include Platform (2015) and Proto (2019).

- Iliass Saoud

Iliass Saoud was born in Halba, Lebanon in 1960 as the sixth of eight children of Wakim and Nadima Saoud. Escaping the Lebanese Civil War in 1977, Iliass migrated to Canada pursued a BA in Mathematics from Dalhouse University in 1982. In 1987 he married Janice Joseph (Fakhry) before settling in Australia to raise his family in 1997, owning a variety of small businesses including the Gaffney Street post office across from the Lincoln Mill’s Centre in Coburg from 2005-2011. Currently, Iliass works part time at a local newsagency and is an avid Bridge player and a dedicated grandfather of one.

- Immy Chuah and The Convoy

The Convoy conjure illustrious soundscapes from the abyss of chaos, revealing hidden worlds of the imagination as the performance takes form and infuses with subjective experience. Using instruments of sound, light and smell, The Convoy enchant space with themes of tension, evolution, entropy and regeneration. Sensorial immersion transports audiences through highly dynamic environments that shift and blend into one single, breathing moment. As entity, rather than singular, Immy Chuah is a guest within The Convoy on unceded land.

- Irene Revell

Irene Revell is a writer and curator who works with artists across sound, text, performance and moving image. Much of her work since 2004 has been with Electra, and she has close involvement with collections including Electra’s Her Noise Archive and Cinenova: Feminist Film + Video. She recently completed her doctoral thesis, Live Materials: Womens Work, Pauline Oliveros and the Feminist Performance Score at CRiSAP where she has taught on the MA Sound Arts since 2014. With Sarah Shin she is currently editing a book on feminisms, sound and listening (Silver Press, 2024). She is an AHRC Postdoctoral Research Associate on Preemptive Listening, at the RCA.

- Isabella Trimboli

Isabella Trimboli is a critic, essayist, editor, and publisher based in Melbourne, Australia. Her essays and criticism have been published widely, for publications including Metrograph Journal, The Saturday Paper, The Monthly, The Guardian, and The Sydney Reviews of Books. She is a 2023 recipient of a Seventh Gallery residency and is the co-founding editor of feminist music journal Gusher.

- Isha Ram Das

Isha Ram Das is a composer and sound artist primarily concerned with ecologies of environment and culture. He works with experimental sound techniques to produce performances, installations and recordings. He was the 2019 recipient of the Lionel Gell Award for Composition, and has scored feature-length films and nationally-touring theatre installations. He has performed at institutions such as the Sydney Opera House; Black Dot Gallery, Melbourne; Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane; Metro Arts, Brisbane; Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney; and Boxcopy, Brisbane.

- Ivan Cheng

Ivan Cheng's recent works are context specific situations, dealing with language and driven by relations with collaborators and hosts. His background as a performer and musician form the basis for using performance as a critical medium. Invested in questions around publics and accessibility, he produces videos, objects, paintings and publications as anchors for the staging of complex and precarious spectacles. His work is presented internationally, and he has initiated project space bologna.cc in Amsterdam since 2017.

- Ivy Alvarez

Ivy Alvarez’s poetry collections include The Everyday English Dictionary, Disturbance, and Mortal. Her latest is Diaspora: Volume L (Paloma Press, 2019). A Fellow of MacDowell Colony (US), and Hawthornden (UK), her work is widely published and anthologised (twice in Best Australian Poems), with poems translated into Russian, Spanish, Japanese and Korean. Born in the Philippines and raised in Australia, she lived in Wales for almost a decade, before arriving in New Zealand in 2014.

- Jacqui Shelton

Jacqui Shelton is an artist and writer born on Barada Barna land, central QLD, and based in Narrm, Melbourne. Her work uses text, performance, film-making and photography to explore the complications of performance and presence, and how voice, language, and image can collaborate or undermine one another. She is especially interested in how emotion and embodied experience can be made public and activated to reveal a complex politics of living-together, and the tensions this makes visible. She has produced exhibitions and performance works in association with institutions including Gertrude Contemporary, the Institute of Modern Art, West Space, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Tarrawarra Museum, and with Channels Festival and Liquid Architecture. Shelton has shown work internationally in Milan at Care-Of, and at NARS Inc in New York City. She teaches photography at Monash University and in the Masters of Media program at RMIT, and holds a PhD from Monash University.

- Jamal Nabulsi

Jamal Nabulsi (he/him) is a Palestinian diaspora activist, writer, scholar, thinker, and rap musician.

- James Hazel

James Hazel is a composer/artist/researcher based on the unceded Gadigal land of the Eora Nation. As someone who lived in an underclass (social-housing) community for fourteen years, James employs extended score practices across sound, music, utterance, and (re)performance to interrogate what it means to live, love, and listen under precarity – stemming from both lived/researched experiences of poverty. As an advocate in this area, James has commissioned several artists from low-SES backgrounds through ADSR Zine.

In recent years, James has 'worked' for the dole; various call centres; and, more recently, as a casual academic in musicology at USYD. In 2021, James was selected as one of the ABC Top 5 Researchers (Arts).

- James Parker

James Parker is an academic at Melbourne Law School and long-time associate curator with Liquid Architecture. His work explores the many relations between law, sound and listening. He is currently working on machine listening with Joel Stern and Sean Dockray.

- James Rushford

James Rushford is an Australian composer-performer who holds a doctorate from the California Institute of the Arts, and was a 2018 fellow at Academy Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart. His work is drawn from a familiarity with specific concrète, improvised, avant-garde and collagist languages. Currently, his work deals with the aesthetic concept of musical shadow. James has been commissioned as a composer by ensembles including the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra (Glasgow), and Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, and regularly performs in Australia and internationally.

- Jana Winderen

Jana Winderen is an artist based in Norway with a background in mathematics, chemistry and fish ecology. Her practice pays particular attention to audio environments and to creatures which are hard for humans to access, both physically and aurally – deep under water, inside ice or in frequency ranges inaudible to the human ear. Her activities include site-specific and spatial audio installations and concerts, which have been exhibited and performed internationally in major institutions and public spaces. Recent work includes 'Listening through the Deadzones' for IHME, Rowingstadium, Helsinki, 'The Art of Listening: Under Water', Lenfest Center for the Arts, Colombia University, New York and Art Basel, Miami, she is currently featured in the Offspring Films series ‘Earthsounds’, for AppleTV+. She releases her audio-visual work on Touch (UK).

- Jannah Quill

Jannah Quill’s deconstructive exploration of electronic instruments and technologies manifests in electronic music production and experimental audio-visual performance and installation. Jannah modifies existing technologies (such as solar panels) into innovative light-to-audio systems, used with software/hardware experimentation and modular synthesis to carve a distinct voice in electronic music and art.

- Jared Davis

Jared Davis is a writer and curator based in London with an interest in independent music, sound culture, and its politics. He is Associate Editor of AQNB and co-host of the editorial platform’s Artist Statement podcast.

- Jasmine Guffond

Jasmine Guffond is an artist and composer working at the interface of social, political, and technical infrastructures. Focused on electronic composition across music and art contexts her practice spans live performance, recording, installation and custom made browser add-ons. Through the sonification of data she addresses the potential of sound to engage with contemporary political questions and engages listening as a situated-knowledge practice.

- Jason De Santolo

Jason De Santolo (Garrwa and Barunggam) is a researcher & creative producer based in the School of Design, University of Technology Sydney, Australia. He has worked with his own communities as an activist and advocate using film and performance, protest and education to bring attention to injustices and design solutions using Indigenous knowledge.

- Jason Waite/Don’t Follow the Wind collective

Jason Waite/Don’t Follow the Wind collective

Jason Waite is a curator, writer, and cultural worker focused on forms of practice producing agency. He is Postdoctoral Fellow of the Arts at Helsinki Collegium Institute of Advanced Studies (University of Helsinki), editor of Art Review Oxford, and an affiliated fellow of the Panel on Planetary Thinking at Justus Liebig University in Giessen. Recently, he is working in crisis sites amidst the detritus of capitalism, looking for tools and radical imaginaries for different ways of living and working together. He is part of the collective Don't Follow the Wind, who are running an ongoing project inside the uninhabited Fukushima exclusion zone. Don’t Follow the Wind (Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group, Kenji Kubota, Jason Waite, Eva and Franco Mattes) came into being on 11 March 2015, on the fourth anniversary of the earthquake and tsunami that triggered the crisis at the nuclear power plant at Fukushima.

- Jazmina Figueroa

Jazmina Figueroa initiated the nineteenth call for Web Residencies and the collaboration between Digital Solitude and Liquid Architecture. Figueroa is a writer and performer.

- Jen Callaway

Jen Callaway is a Melbourne musician, sound and performance artist, photographer, and community services worker raised in various parts of Tasmania. Current projects include bands Is There a Hotline?, Propolis, Snacks and Hi God People; and upcoming film Here at the End, by Campbell Walker, as actor/co-writer.

- Jennifer Gabrys

- Jessica Aszodi

Jessica Aszodi is an Australian-born, London-based vocalist who has premiered many new pieces, performed work that has lain dormant for centuries, and sung roles ranging from standard operatic repertoire to artistic collaborations. She has been a soloist with ensembles including ICE; the Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide Symphony Orchestras; and San Diego and Chicago Symphony Orchestras’ chamber series. Aszodi can be heard on numerous recordings and has sung in festivals around the world. She holds a Doctorate of Musical Arts from the Queensland Conservatorium, an MFA from the University of California, and is co-director of the Resonant Bodies Festival (Australia), and artistic associate of BIFEM.

- Jessie Scott

Jessie Scott is a practising video artist, writer, programmer and producer who works across the spectrum of screen culture in Melbourne. She is a founding member of audiovisual art collective Tape Projects, and co-directed and founded the inaugural Channels Video Art Festival in 2013.

- Jim Denley

Jim Denley is one of Australia's foremost improvisers. Over a career spanning four decades his work has emphasised the use of recording technologies, co-creation, and a concern with site-specificity.

- Joee Mejias

Joee Mejias is a musician and video artist from Manila. She is co-producer of WSK, the first and only international festival of digital arts and new media in the Philippines and co-founder of HERESY, a new platform for women in sound and multimedia. She performs as Joee & I: her avant-pop electronica solo project.

- Joel Sherwood Spring

Joel Sherwood Spring is a Wiradjuri man raised between Redfern and Alice Springs who works across research, activism, architecture, installation and speculative projects. At present, his work focuses on the contested narratives of Sydney’s and Australia’s urban culture and indigenous history in the face of ongoing colonisation.

- Joel Stern

Joel Stern is a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the School of Media and Communication at RMIT, and an Associate Editor at Disclaimer. With a background in experimental music, Stern’s work — spanning research, curation, and art — focuses on practices of sound and listening and how these shape our contemporary worlds. From 2013-2022 he was the Artistic Director of Liquid Architecture.

- Johnny Chang

Berlin-based composer-performer Johnny Chang engages in extended explorations surrounding the relationships of sound/listening and the in-between areas of improvisation, composition and performance. Johnny is part of the Wandelweiser composers collective and currently collaborates with: Catherine Lamb (Viola Torros project), Mike Majkowski (illogical harmonies), Phill Niblock, Samuel Dunscombe, Derek Shirley and others.

- Jolyon Jones

Jolyon Jones is a Berlin-based student of fine arts at the University of Arts Berlin. He works primarily between sculpture, drawing, print media and sound. With an interest in practices of labour, Jolyon draws upon his background in anthropology exploring embedded concepts through research and architecture and the latent possibilities of everyday materials such as concrete, graphite, and silicone to access speculative narratives and the construction of mementos.

- Jon Watts

Jon Watts is a Melbourne/Naarm based musician, designer, 3D artist and animator. His music has been released through cult labels SUMAC and Butter Sessions, and he is currently Senior Multimedia Installer at the National Gallery of Victoria.

- Josten Myburgh

Josten Myburgh is a musician based on Whadjuk Noongar boodja country who plays with techniques from the worlds of electro-acoustic music, radio art, free improvisation, field recording and experimental composition. He co-directs exploratory music label Tone List and the Audible Edge festival. He has performed in South Africa, the United States, and throughout South East Asia, Europe and Australia. He is a Schenberg Fellow and a student of Antoine Beuger and Michael Pisaro.

- Joy Zhou

Joy Zhou is a China born emerging artist and design practitioner based in Naarm/Melbourne. Informed by their background in Interior Design, Joy’s practice entails gestures of queering which unfold encounters and events that draw relationships between people, places, and spaces.

- Julius Killerby

Julius Killerby is an artist living and working in London. His work focuses on the psychological ripple effects of certain cultural and societal transformations. Part of Julius’ practice also includes portraiture, and in 2017 he was nominated as a finalist in the Archibald Prize for his portrait of Paul Little. His work has been exhibited at VCA Art Space, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Art Gallery of Ballarat, and Geelong Gallery.

- Katie West

Katie West is a multi-disciplinary artist who lives on Noongar Ballardong boodja and belongs to the Yindjibarndi people of the Pilbara tablelands in Western Australia. The process and notion of naturally dyeing fabric underpin her practice – the rhythm of walking, gathering, bundling, boiling up water and infusing materials with plant matter. The objects, installations and happenings that Katie creates invite attention to the ways we weave our stories, places, histories, and futures.

- Kaz Therese

Kaz Therese (they/them) grew up on Darug land in Mt Druitt, Western Sydney. They are an interdisciplinary artist and cultural leader with a practice grounded in performance, activism and community building. Their work is inspired by place and narrative from working class & underclass settings. From 2013- 2020 they were the Artistic Director of PYT Fairfield. Kaz directed the Helpmann nominated PLAYLIST (premiered 2018), UnWrapped, Sydney Opera House (2019) Other works include TRIBUNAL presented at Griffin Theatre, ArtsHouse Melbourne, Sydney Opera House, Sydney Festival; WOMEN OF FAIRFIELD with MCA C3West and STARTTS, winning the Sydney Myer Arts & Cultural Award for Best Arts Program (2016).Kaz is founder of FUNPARK ,Mt Druitt (Sydney Festival 2014) and a graduate of the 2019 Australia Council Cultural Leadership program.

- Kengné Téguia

Kengné Téguia is a Black Deaf HIV+ cyborg artist, who works from sound deafinitely. #TheBLACKRevolutionwillbeDEAFinitelyLoud

- Kenneth Constance Loe

Kenneth Constance Loe (he/they) is an artist, writer, and performer from Singapore, and currently based in Vienna, Austria.

- Khalid Abdalla

Khalid Abdalla is an actor, producer, writer and filmmaker, known for his performances in The Crown as Dodi Fayed, The Kite Runner, United 93 and Green Zone. He produced and starred in the Egyptian feature In the Last Days of the City, and appears in Jehane Noujaim’s Oscar nominated documentary about the 2011 Egyptian revolution The Square. He has recently completed his first play, Nowhere, produced by Fuel Theatre. Khalid is a founding member of three cultural initiatives in Cairo – Cimatheque, Zero Production and Mosireen.

- kirby

kirby is a fledgling. They garden, listen, and learn in Wurundjeri Country. kirby’s ecological listening project Local Time combines field recording and experimental web development to explore more-than-human neighborhood entanglements.

- KT Spit

Kt Spit (Katie Collins) is an artist and musician based in Narrm (Melbourne). Lyrically and visually her work explores subcultural narratives and challenges dominant representations of loss, grief, and true love. In 2015 Kt independently released her debut album, Combluotion, and in 2019 will release a visual album entitled Kill the King.

- Kynan Tan

Kynan Tan is an artist interested in the relations and conditions of computational systems, with a focus on data, algorithm, networks, materiality, control, and affect. These areas are explored using computer-generated artworks that take the form of simulations, video, sound, 3d prints, text, code, and generative algorithms.

- Las Chinas

Las Chinas is the cosmic coincidences led to the meeting of Chileans Sarita Gálvez and Camila Marambio in Melbourne. Their shared reverence for the ancestral flautón chino from the Andes Mountains lead to playful explorations of its unique dissonant sounds and thereafter to experimenting with atonal signing and other technologies of the spirit.

Influenced by Chilean feminist poet Cecilia Vicuña, the now deceased poet Fidel Sepúlveda, the musical ensemble La Chimuchina and the chino bands from the townships of La Canela and Andacollo, Las Chinas honours the ancestral tradition by enacting the principle of tearing each other apart.

- Laura McLean

Laura McLean is a curator, writer, and researcher based in Naarm Melbourne. She is an Associate Curator at Liquid Architecture, member of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society (ADM+S), and is currently undertaking a PhD in Curatorial Practice at MADA, Monash University. Past curatorial projects include CIVICS, Maroondah Federation Estate Gallery, Melbourne (2020); Startup States, Sarai-CSDS, Delhi (2019); and Contingent Movements Archive, Maldives Pavilion, 55th Venice Biennale (2013). Her writing is included in edited books published by Arena, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the MIT Press, among others, and has been published by journals including Eyeline, Realtime, HKW Technosphere Magazine, and ArtAsiaPacific.

- Laurie May

Originally from the Gulf of Carpentaria, Laurie May has made home here in the desert in Mparntwe. With Aboriginal ancestry from Central Queensland from her father and New Zealand heritage from her ma they have the saltwater, the red dirt and long white cloud in their veins. Embracing trauma and a troubled youth to bring you anti-capitalist poetry that makes you think. Laurie is also the Festival Director for the Red Dirt Poetry Festival and an award winning event producer.

- Leighton Craig

Leighton Craig is an artist living in Meanjin/Brisbane. He has been in a number of bands (The Lost Domain, G55, The Deadnotes et al) and is currently a member of the duo Primitive Motion with Sandra Selig.

- Liang Luscombe

Liang Luscombe is a Naarm/Melbourne-based visual artist whose practice encompasses painting, sculpture and moving image that engage in a process of generative questioning of how media and film affect audiences.

- Lin Chi-Wei

Lin Chi-Wei is a legend of Taiwanese sonic art, whose practice incorporates folklore culture, noise, ritual, and audience participation.

- Lisa Lerkenfeldt

Lisa Lerkenfeldt is a multi-disciplinary artist working in sound, gesture and performance. Central to her practice is languages of improvisation and intimacy with technology. Traces of a personal discipline and form of graphic notation are introduced in the online exhibition 14 Gestures. The associated recorded work Collagen (Shelter Press, 2020) disrupts the role of the common hair comb through gesture and sound.

- Lucreccia Quintanilla

Lucreccia Quintailla is a multidisciplinary artist, DJ, educator, co-director of Liquid Architecture, and a sound system operator. She is interested in sound and collectivity and collaboration.

- Luisa Lana

Luisa Lana was born in Australia in 1953. Her mother Nannina had arrived in Australia in 1950 with a 3 month old son, and worked for many years on the sewing room floors and her father Angelo worked on the docks where he helped unionise the Italian workforce. Luisa and her brother were latchkey kids, as they looked after themselves in the morning and ran the ‘Continental’ deli in the evenings. Luisa attained a teaching degree, then a postgrad in Social Sciences, and twice studied Italian at The University for Foreigners in Perugia, Italy. Luisa married Luigino Lana, a Venetian migrant who operated a mechanic business in Brunswick for over 30 years. She devoted her life to being an educator and a mother, teaching Italian to English speakers and English to generations of migrants from around the world. Currently Luisa is translating her father's memoirs from Italian to English, and enjoying being a Nonna.

- Luke Conroy

Luke Conroy is a Tasmanian multidisciplinary artist currently based in The Netherlands. With a background in sociology and arts education, Luke’s artistic practice engages with socio-cultural topics in meaningful yet playful ways, utilising humour and irony as essential tools for critical reflection and expression. The outcome of his work utilises an ever-evolving multimedia and audio-visual practice which includes photography, digital-art, video, sound, VR, textile, text, and installation.

- Lu Yang

Lu Yang (b. Shanghai, China) is a multimedia artist based in Shanghai. Mortality, androgyny, hysteria, existentialism and spiritual neurology feed Lu’s jarring and at times morbid fantasies. Also taking inspiration and resources from Anime, gaming and Sci-fi subcultures, Lu explores his fantasies through mediums including 3D animation, immersive video game installation, holographic, live performances, virtual reality, and computer programming. Lu has collaborated with scientists, psychologists, performers, designers, experimental composers, Pop Music producers, robotics labs, and celebrities throughout his practice.

Lu Yang has held exhibitions at UCCA (Beijing), MWoods (Beijing), Cc Foundation (Shanghai), Spiral (Tokyo), Fukuoka Museum of Asian Art (Fukuoka, Japan), Société (Berlin), MOCA Cleveland (Cleveland, Ohio). He has participated in several international biennials and triennials such as 2021 Asia Society Triennial (New York), 2012 & 2018 Shanghai Biennial, 2018 Athens Biennale, 2016 Liverpool Biennial, 2016 International Digital Art Biennale (Montreal), Chinese Pavilion of the 56th Venice Biennale, and 2014 Fukuoka Triennial. In 2020, Lu Yang was included in Centre Pompidou’s exhibition Neurons, simulated intelligence in Paris. In 2019, Lu was the winner of the 8th BMW Art Journey and started the Yang Digital Incarnation project.

- Makiko Yamamoto

Makiko Yamamoto

makik markie yammamoroto

Mama

Kik

Makiki

Yammer matah

Ma

Ki

ko

- Mandy Nicholson

Mandy Nicholson is a Wurundjeri-willam (Wurundjeri-baluk patriline) artist and Traditional Custodian of Melbourne and surrounds. Mandy also has connections to the Dja Dja wurrung and Ngurai illam wurrung language groups of the Central/Eastern Kulin Nation. Mandy gained a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in Aboriginal Archaeology in 2011, worked for the Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages for six years and is now a PhD candidate studying how Aboriginal people connect to Country, Off Country.

- Mara Schwerdtfeger

Mara Schwerdtfeger is a composer / curator / audio producer based in Eora / Sydney. She plays the viola and collaborates with her laptop to create live performances and recorded pieces for film, dance, and gallery spaces.

- Margarida Mendes

Margarida Mendes is a researcher, curator, artist and educator, exploring the overlap between systems thinking, experimental film, sound practices and ecopedagogy. She creates transdisciplinary forums, exhibitions and experiential works where alternative modes of education and sensory practices may catalyse political imagination and restorative action. Mendes has long been involved in anti-extraction activism collaborating with marine NGOs, Universities, and institutions of the art world. She holds a PhD in Research Architecture by the Department of Visual Cultures, Goldsmiths University of London and is a member of Natural Contract Lab, a transdisciplinary collective of lawyers and artists working on restorative justice and rights of nature across Europe.

- Mariah Reodica

Mariah Reodica is a musician, and cultural journalist based in the Philippines. She founded Anecdotal Records, an aural research initiative mapping music and technology rooted in local and lived experiences through writing, curating live performances, and workshops.

She has taught film at the University of the Philippines and De La Salle-College of St. Benilde. Reodica received the Prince Claus SEED Fund Award, Purita Kalaw-Ledesma Prize for Art Criticism at the Ateneo Art Awards and the Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards for Literature. Her byline has appeared in Rolling Stone, Vogue, and Billboard, among other publications.

- Maria Moles

Maria Moles is an Australian drummer, composer and producer based in Narrm/Melbourne.

- Martina Becherucci

Martina Becherucci graduated in Cultural Heritage at the University of Milan and is currently completing her studies with a Master degree in Economics and Management of Arts and Cultural Activities at the Ca' Foscari University of Venice. Martina loves being in contact with visitors in museums and galleries, during temporary exhibitions and cultural events.

- Martyn Reyes

Martyn Reyes is a Filipino-Australian writer and artist based in Madrid. His work can be found in the Sydney Review of Books, Kill Your Darlings, SBS Voices, LIMINAL Magazine and more. He is currently working on a book-length project.

- Mat Dryhurst

Mat Dryhurst is an artist who releases music and artworks solo and in conjunction with Holly Herndon and the record label PAN. Dryhurst developed the decentralised publishing framework Saga, which enables creators to claim ownership of each space in which their work appears online, and a number of audio plays that derive their narrative from the personal information of listeners. He lectures on issues of music, technology, and ideology at NYU, and advises the blockchain-based platform co-operative Resonate.is.

- Mat Spisbah

Mat Spisbah is a New Media curator with a unique portfolio of programming that seeks to integrate non-traditional artistic methods and emerging technologies. Having lived in Hong Kong for 14 years, he is connected to the region’s art and culture, and has created professional networks with artists, curators, galleries, promoters and industry professionals across Australasia. Portfolio highlights include the debut Australian performances of north Asian artists including: Howie Lee, Rui Ho, Meuko Meuko, Pan Daijing, Alex Zhang Hungtai, Tzusing, and Gabber Modus Operandi.

- Mattin

Mattin is a cross disciplinary artist working with noise, improvisation and dissonance. His work Social Dissonance was presented at documenta 14 in 2017 in Kassel and Athens.

- Mazen Kerbaj